Source: World War I Centennial Commission

World War I was a war unlike any other, with weapons the like of which the world had never seen before. Advancements in technology had made war far more deadlier and permanently changed the way we waged war. Read through the resources below to learn more about the weapons used in World War I.

The opening months of the First World War caused profound shock due to the huge casualties caused by modern weapons. Losses on all fronts for the year 1914 topped five million, with a million men killed. This was a scale of violence unknown in any previous war. The cause was to be found in the lethal combination of mass armies and modern weaponry. Chief among that latter was quick-firing artillery. This used recuperating mechanisms to absorb recoil and return the barrel to firing position after each shot. With no need to re-aim the gun between shots, the rate of fire was greatly increased. Read through this website to learn more.

This website lists and describes some of the main weapons used in World War I.

Although the Australian Army was still being formed when the war began, weaponry between the six Australian states had been standardised since Federation in 1901. The equipment used by the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was mostly the same as the British Army and the armies of the other British dominions. Read through this website to learn about the weapons the Australian Army was supplied with in World War I.

The devastating firepower of modern weapons helped create the trench stalemate on the Western Front during the First World War. Armies were forced to adapt their tactics and pursue new technologies as a way of breaking the deadlock. This article explores some of the weapons used and developed by the British Army during the conflict.

The static battlefield on the Western Front led to the development of new and more effective weapons, and the improvement of old ones. Read through this article to learn about some of the weapons used.

There were major developments in technology during World War One. New weapons and machines changed the way war was fought forever. Read through this website to learn more.

World War I was a war of artillery - The Big Guns. Rolling barrages destroyed the earth of France and Belgium and the lives of many. Millions of shells were fired in single battles, with one million shells alone fired by the Germans at the French Army in the first day at the 1916 battle of Verdun, France. Read through this article to learn more about the artillery used in World War One.

This article looks at some of the major weapons used in World War One.

The machine gun, which so came to dominate and even to personify the battlefields of World War One, was a fairly primitive device when general war began in August 1914. Machine guns of all armies were largely of the heavy variety and decidedly ill-suited to portability for use by rapidly advancing infantry troops. Read through this website to learn more.

Senior Curator Paul Cornish looks at the developments in weaponry technology and strategy that led to the modern warfare of World War One, which was characterised by deadly new weapons, trench deadlocks, and immense numbers of casualties.

One of the enduring hallmarks of WWI was the large-scale use of chemical weapons, commonly called, simply, ‘gas’. Although chemical warfare caused less than 1% of the total deaths in this war, the ‘psy-war’ or fear factor was formidable. Thus, chemical warfare with gases was subsequently absolutely prohibited by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. It has occasionally been used since then but never in WWI quantities.

The trench warfare of the Western Front encouraged the development of new weaponry to break the stalemate. Poison gas was one such development. Read through this website to learn more.

The first large-scale use of lethal poison gas on the battlefield was by the Germans on 22 April 1915 during the Battle of Second Ypres. Read through this article to learn more.

Gas soon became a routine feature of trench warfare, horrifying soldiers more than any conventional weapon. But was it actually as deadly as its terrible reputation suggests?

Barbed wire and machine-guns stopped many Allied attacks with heavy casualties in 1915 and early 1916. The British turned to armoured vehicles as one way to cross No Man’s Land and break through the enemy trench system. Read through this article to learn more.

One hundred years ago in September, a small group of machines, dreamt of by Leonardo, but hitherto unseen on the field of battle, chugged along in the predawn darkness, just south of the town Flers, France, in the region of the Somme. These machines, whose descendants would, in another war, become known for their lightning speed, crawled along at under four miles per hour, picking their way through a landscape of shattered tree stumps and mud. As the dawn broke, a single machine made its way through ranks of soldiers, passed into the churned wasteland between the lines, began to fire, and the age of the tank began. Read through this article to learn more.

The concept of a vehicle to provide troops with both mobile protection and firepower was not a new one. But in the First World War, the increasing availability of the internal combustion engine, armour plate and the continuous track, as well as the problem of trench warfare, combined to facilitate the production of the tank. Read through this article to learn more.

On 31 May 1918, a small tank designed by a famous French car maker and a brilliant army officer saw its first action. Its inspired design still lives on in the tanks of today, 100 years later. Read through this article to learn more.

The war drove scientific and technological initiative on an unprecedented scale. Innovation on both sides created more destructive and effective weapons. Communications, medicine and transportation were also advanced. But not all inventions achieved their intended goals. Read through this article to learn more.

The flamethrower, which brought terror to French and British soldiers when used by the German army in the early phases of the First World War in 1914 and 1915 (and which was quickly adopted by both) was by no means a particularly innovative weapon. Read through this website to learn more.

Britain's blockade across the North Sea and the English Channel cut the flow of war supplies, food, and fuel to Germany during World War I. Germany retaliated by using its submarines to destroy neutral ships that were supplying the Allies. The formidable U-boats (unterseeboots) prowled the Atlantic armed with torpedoes. They were Germany’s only weapon of advantage as Britain effectively blocked German ports to supplies. The goal was to starve Britain before the British blockade defeated Germany. Read through this article to learn more.

Submarines played a significant military role for the first time during the First World War. Both the British and German navies made use of their submarines against enemy warships from the outset. Read through this article to hear firsthand accounts of fighting against submarines in World War One.

When the Commonwealth was proclaimed in 1901, submarines were beginning to appear in the Royal Navy, where their introduction had been opposed for a long time. But with the growth of the German Navy at the outbreak of World War One, Australia began investing in submarines.

Before the 20th Century, civilians in Britain were largely unaffected by war, but this was to change on 19 January 1915 with the first air attacks of World War One by the German Zeppelin. In this article, historian and aerial specialist Ben Robinson has traced the attacks for Inside Out East.

Before the 20th century, civilians in Britain had been largely unaffected by war. Previous overseas wars rarely touched British shores. The First World War was to change all that. Historians have described it as a ‘total war’, a global war which involved both civilians and the armed services on a massive scale. Read through this article to learn more.

Artillery was the most destructive weapon on the Western Front. The ability to destroy enemy troop concentrations, wire, guns and fortified positions with artillery became key to any successful operation. The guns could fire shrapnel or high explosive shells, as well as poison gas.

Introduced in 1904 as a result of deliberations by the Royal Artillery following the Boer War (1899-1902), the 18 pounder was a heavier version of the 13 pounder Horse Artillery weapon. Over 1,000 had been made by the start of World War One (1914-1918) where it was seen as the most effective light field gun. Over 8,000 were eventually manufactured during the war and between them fired 100 million shells. With a crew of ten men, it could fire 18-pound shrapnel, high explosive or smoke shells up to six kilometres (over 6,500 yards).

During the Battle of the Somme (1916) the British fired over 15 million shells. Of those, some 10 million were fired by 18-pounders. With an experienced crew and in good conditions, the 18-pounder could fire at a remarkable 30 rounds a minute. The gun saw service in the Middle East, Gallipoli and the Balkans, as well as on the Western Front.

The Vickers .303 inch Class C was a commercially-available, water-cooled machine gun which was trialled by the British Army from 1910. Following a few changes, it was adopted by the British Army as the Vickers Mark 1 on 26th November 1912 and became the standard machine gun of the British and Commonwealth forces. It weighs about 28 lbs when empty of water and typically required a six to eight-man team to transport and operate them and their associated accessories and ammunition.

The Vickers Mark 1 machine gun was used in all theatres of the First World War and it was famed for its reliability. It could fire over 600 rounds per minute and had a range of 4,500 yards (or over 4 kilometres). With proper handling, the Vickers could sustain a rate of fire for hours, providing a necessary supply of fabric belts of ammunition, spare barrels and cooling water was available. It holds about 7.5 pints of water. When there was insufficient water to hand, soldiers would urinate in the water jacket to keep the gun cool!

Vickers machine guns were one of the deadliest weapons of the Western Front and are considered one of the finest machine-guns ever made. In August 1916 the 100th Company of the Machine Gun Corps fired their ten Vickers guns continuously for 12 hours on the Western Front. The Vickers .303 continued to be used by the British Army in the 1960s. When it was withdrawn from service in 1968, it was given a full military funeral at Bisley.

The Lewis Gun, with its distinctive barrel cooling shroud and top-mounted drum magazine, was the British Army's most widely used machine gun during World War One (1914-1918). Each Lewis Gun required a team of two gunners, one to fire and one to carry ammunition and reload. All of the members of an infantry platoon would be trained in the use of the Lewis Gun so that they could take over if the usual gunners were killed or wounded.

This image depicts a Sopwith Snipe of 43 Squadron, Royal Air Fore, with Lieutenant E. Mulcair standing in front. This squadron, based at at Fienvillers in France, was one of the first to be equipped with the new fighter, which replaced its Sopwith Camels in August 1918.

Mortars were originally large calibre weapons used for siege warfare, but during World War One (1914-1918) armies developed lighter infantry mortars for use in the trenches. The British Army's Stokes Mortar consisted of a smoothbore metal tube fixed to an anti-recoil base plate. When a mortar bomb was dropped into the tube, an impact sensitive primer in the base of the bomb would make contact with a firing pin at the bottom of the tube, and detonate, firing the bomb towards the target. The Stokes could fire around 20 bombs per minute and had a maximum range of 1,200 yards.

Australians load a trench mortar, nicknamed 'the flying pig', during the Battle of Pozieres Ridge (23 July-4 August 1916). The location is the Chalk Pit, situated to the south of Pozieres. Most of the troops involved in this operation belonged to the I Anzac Corps.

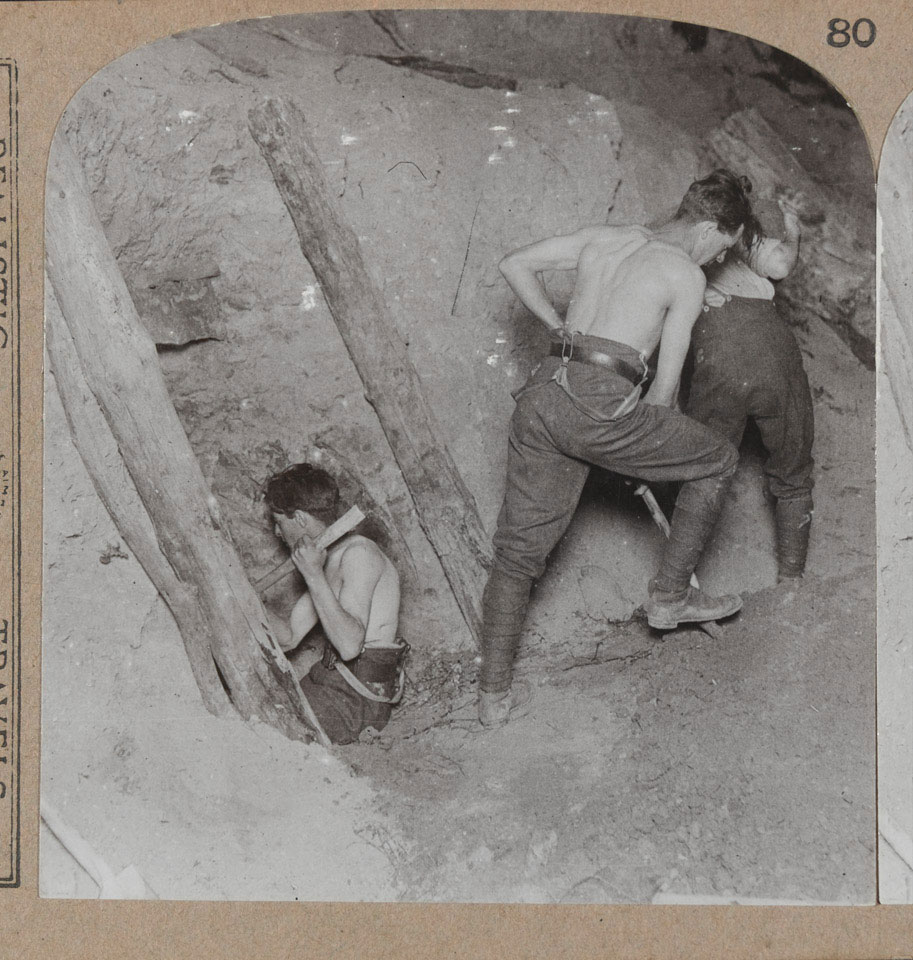

The mine was dug under the German lines at Hawthorn Redoubt. It was fired 10 minutes before the assault at Beaumont Hamel on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916. Around 45,000 pounds of Ammonal exploded. The mine created a crater 130 feet across by 58 feet deep.

Tunnelling and mining operations were used to attack enemy positions by digging underneath them and then destroying them with explosive mines. This bag originally contained explosives and was part of a three-ton charge laid in the Durand Mine during an attack at Vimy Ridge on 9 April 1917. The mine was not detonated during the operation.

Tunneling and mining operations were used to attack enemy positions by digging underneath them and then destroying them with explosive mines. Much of the excavation work was done by special Royal Engineers units formed from Welsh and Durham miners. Sometimes miners would meet and fight German tunnellers underground as their tunnels intercepted enemy works.

Experiments with new smokeless cartridges, bolt-actions and magazine loading had resulted in the introduction, in 1903, of the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield, the rifle which would arm the British Army for two World Wars. Firing a small-calibre bullet to a maximum range of 2,800 yards, the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield was the infantryman's definitive weapon. In the initial battles of the World War the German troops believed that they were facing machine guns rather than rapid rifle fire.

The Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Rifle was designed to be fitted with a bayonet. The addition of this fearsome blade gave the Tommy a reach of over a metre in hand-to-hand combat. However, a rifle fitted with a bayonet could prove unwieldy in the close confines of a trench system. Many soldiers therefore preferred to use improvised clubs, knives or knuckledusters. The bayonet was nevertheless a handy tool and soldiers were as likely to use them for cooking and eating as fighting.

The introduction of gas warfare in 1915 created an urgent need for protective equipment to counter its effects. Accordingly, the British Army soon developed a range of gas helmets based on fabric bags and hoods that had been treated with anti-gas chemicals. These were later replaced by the small box filter respirator which provided greater protection.

The introduction of gas warfare on the Western Front in 1915 meant that rattles, horns and whistles were soon adopted as means of warning troops and giving them time to put on protective equipment during gas attacks. Rattles could also be used to simulate machine-gun fire.

The machine-gun was one of the dominant weapons on the First World War battlefield. When established in a fixed defensive position and sited specifically to cover potential enemy attack routes it was a fearsome weapon. Infantry assaults upon such positions invariably resulted in high casualties.

Trench clubs were home made weapons used by First World War (1914-1918) soldiers during trench raids. The could be used to quietly kill or knock unconscious enemy troops in the confined spaces of a trench. Most were made of wood and fitted with a metal object at the striking end. They were used alongside other 'silent' weapons such as knives, bayonets and axes.

The Mark IV was an up-armoured version of the Mark I tank. To improve safety, its fuel was also stored in a single external tank located between the rear track horns. The female Mark IV was armed with six .303 Lewis machine guns and the male with two six pounder guns and four Lewis guns.

The world's first anti-tank rifle was developed near the end of World War One (1914-1918) in 1918, it had an effective range of 500 metres. Bullets like this could penetrate over two centimetres of armour plate when fired at 100 metres.

The No 1 was the first British grenade of World War One (1914-1918). It consisted of a canister with a wooden handle. It was armed by removing a safety pin through the top. When thrown, the handle and attached linen streamer ensured it landed nose down so that the striker was forced into the detonator. Soldiers disliked the Mark 1 as it was liable to explode prematurely if knocked against something when being thrown. This was a real danger in the confined space of a trench.

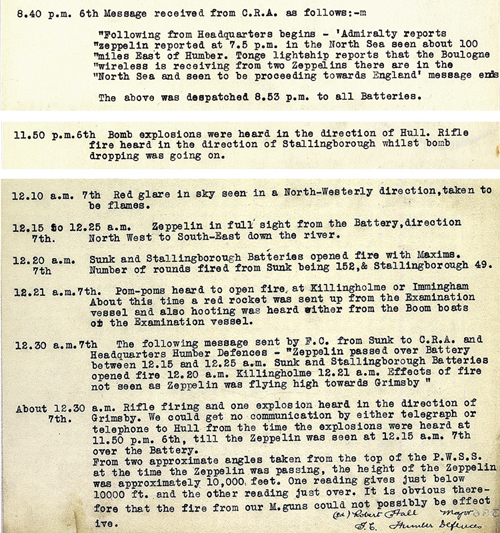

8.40 p.m. 6th Message received from C.R.A. as follows:-

“Following from Headquarters begins – ‘Admiralty reports “zeppelin reported at 7.5 p.m. in the North Sea sean about 100 “miles East of Humber. Tonge lightship reports that the Boulogne “wireless is receiving from two Zeppelins there are in the “North Sea and seen to be proceeding towards England’ message ends

The above was dispatched 8.53 p.m. to all Batteries.

11.50 p.m.6th Bomb explosions were heard in the direction of Hull. Rifle fire heard in the direction of Sallingborough whilst bomb dropping was going on.

12.10 a.m. 7th Red glare in sky seen in a North-Westerly direction, taken to be flames.

12.15 to 12.25 a.m. 7th Zeppelin in ful sight from the Battery, direction North west to South -East down the river.

12.20 a.m. 7th Sunk and Stallingborough Batteries opened fire with Maxims. Number of rounds fired from Sunk being 152, & Stallingborough 49.

12.21 a.m. 7th Pom-poms heard to open fire at Killingholme or Immingham About this time a red rocket was sent up from the Examination vessel and also hooting was heard either from the Boom boats of the Examination vessel.

12.30 a.m. 7th The following message sent by F.C. from Sunk to C.R.A. and Headquarters Humber Defences – “Zeppelin passed over Battery between 12.15 and 12.25 a.m. Sunk and Stallingborough Batteries opened fire 12.20 a.m. Killingholme 12.21 a.m. Effects of fire not seen as Zeppelin was flying high towards Grimsby”

About 12.30a.m. 7th. Rifle firing and one explosion heard in the direction of Grimsby, We could get no communication by either telegraph or telephone to Hull from the time the explosions were heard at 11.50p.m. 6th, till the Zeppelin was seen at 12.15 a.m. 7th over the Battery.

From two approximate angles taken from the tip of the P.W.S.S. at the time the Zeppelin was passing, the height of the Zeppelin was approximately 10,000 feet. One reading gives just below 10000 ft. and the other reading just over. It is obvious therefore that the fire from our M.guns could not possibly be effective.

Maxim: a machine-gun

pom-pom: nickname for a machine-gun

Sunk: gun battery 5 miles south east of Hull

Stallingborough: gun battery 10 miles south east of Hull

Killingholme, Immingham: gun batteries 8 and 9 miles south east of Hull

CRA = Commander, Royal Artillery

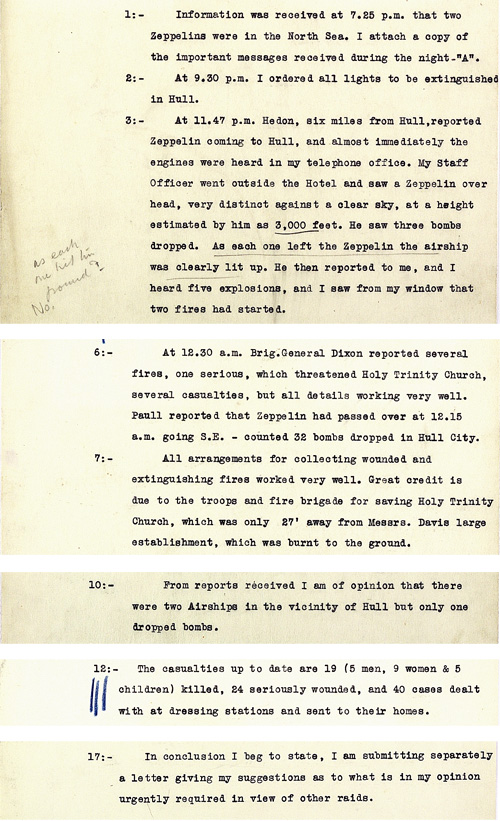

1:- Information was received at 7.25 p.m. that two Zeppelins were in the North Sea. I attach a copy of the important messages received during the night = “A”.

2:- At 9.30 p.m. I ordered all lights to be extinguished in Hull.

3:- At 11.47 p.m. Hedon, six miles from Hull, reported Zeppelin coming to Hull, and almost immediately, the engines were heard in my telephone office. My Staff Officer went outside the Hotel and saw a Zeppelin over head, very distinct against a clear sky, at a height estimated by him as 3,000 feet. He saw three bombs dropped. As each one left the Zeppelin the airship was clearly lit up. He then reported to me, and I heard five explosions, and I saw from my window that two fires had started. […]

6:- At 12.30 a.m. Brig.General Dixon reported several fires, one serious, which threatened Holy Trinity Church, several casualties, but all details working very well. Paull reported that the Zeppelin had passed over at 12.15 a.m. going S.E. – counted 32 bombs dropped in Hull City.

7:- All arrangements for collecting wounded and extinguishing fires worked very well. Great credit is due to the troops and fire brigade for saving Hold Trinity Church, which was only 27′ away from Messes. Davis large establishment, which was burnt to the ground. […]

10:- From reports received I am of opinion that there were two Airships in the vicinity of Hull, but only one dropped bombs.

12:- The casualties up to date are 19 (5 men, 9 women & 5 children) killed, 24 seriously wounded, and 40 cases dealt with at dressing stations and sent to their homes. […]

17:- In conclusion I beg to state, I am submitting seperately a letter giving my suggestions as to what is in my opinion urgently required in view of other raids.

First World War

by

First World War

by

Frightful first World War

by

Frightful first World War

by

Living through World War I

by

Living through World War I

by

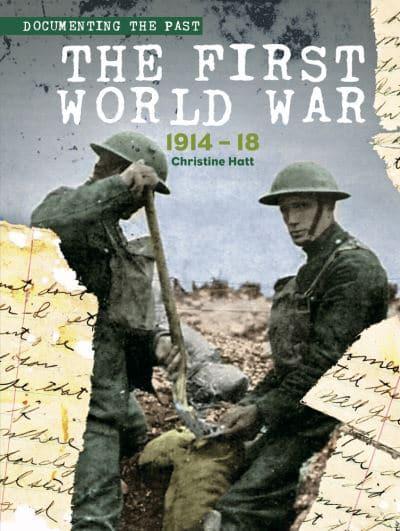

The First World War 1914-18

by

The First World War 1914-18

by

To end all wars : the First World War 1914-1918

by

To end all wars : the First World War 1914-1918

by

World War 1

by

World War 1

by

World War I

by

World War I

by

World War I

by

World War I

by

World War I : 1914-1918

by

World War I : 1914-1918

by