Source: Britannica

Bringing an end to the Roaring 20s, the Great Depression was the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world. Lasting almost 10 years (from late 1929 until about 1939) and affecting nearly every country in the world, it was marked by steep declines in industrial production and in prices (deflation), mass unemployment, banking panics, and sharp increases in rates of poverty and homelessness. Read through the resources below to learn more.

Beach pavilion at Mentone. Built by ‘suso’ workers in 1938. Original roof was made from shingles but replaced in 2011 with corrugated iron.

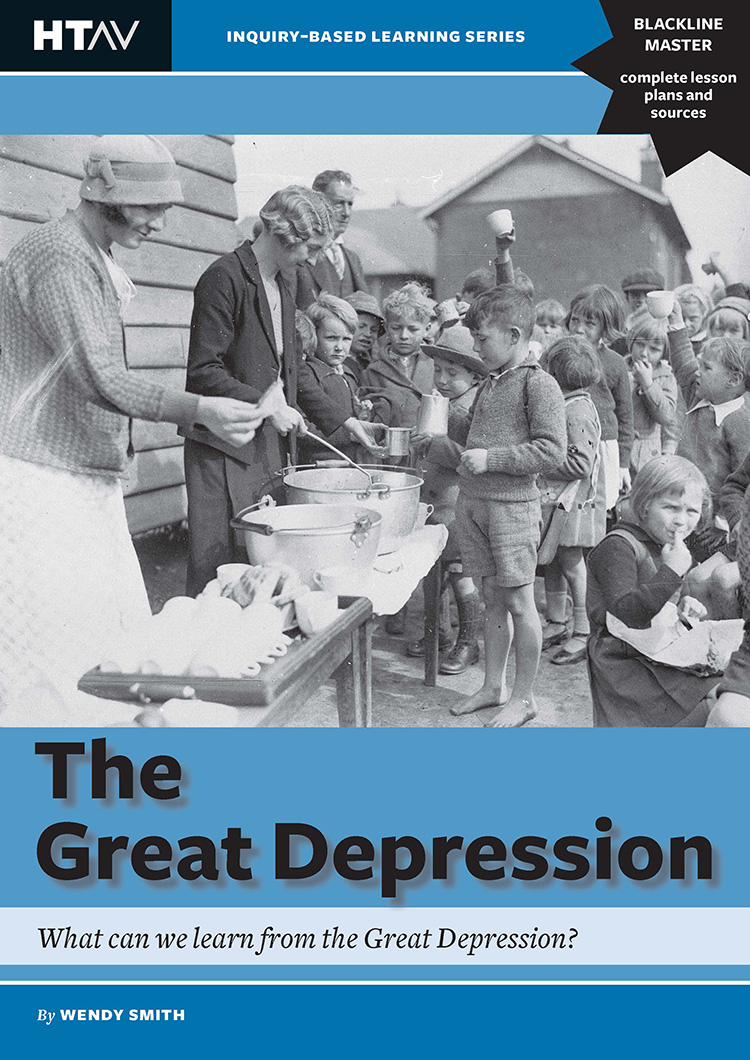

Children and young people were some of the hardest hit by malnutrition, and were especially vulnerable to hunger as they were reliant on parents and care givers to provide.

Squatters' shacks along the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon. Many of the men living here during the winter work in the nearby orchards of the Williamette and Yakima Valley in the summer

Click through this link to read Herbert Hoover's address at Madison Square Garden New York City, October 31, 1932. As the 1932 presidential campaign drew to a close, Hoover fired back against his Democratic challenger in a speech at Madison Square Garden. He seized on proposals made by Democratic leaders in Congress, and Roosevelt’s own words from the Commonwealth Club address, to portray the opposition as dangerously irresponsible and committed to a philosophy at odds with that of the American Founding. The president reminded his listeners of the progress made in the past thirty years, and while he admitted that the past three years had brought considerable distress, he asserted that the system established by the Founders in the Constitution had proven capable of weathering the worst of the crisis.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/e2/32e28b8b-ff2d-4d67-a9b2-1f0fbbe2c5a0/8b29527v.jpg)

Portrait of Florence Thompson, aged 32, that was part of Lange's "Migrant Mother" series. Lange's notes detailed that the family had "seven hungry children," including the one pictured here.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Dust_Storms__Kodak_view_of_a_dusk_storm_Baca_Co._Colorado_Easter_Sunday_1935__Photo_by_N.R._Stone_-_NARA_-_195659.tif-d63dfeb61fa745f8aacbe26ae78a7de6.jpg)

Hot and dry weather over several years brought dust storms that devastated the Great Plains states, and they came to be known as the Dust Bowl. It affected parts of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado and Kansas. During the drought from 1934 to 1937, the intense dust storms, called black blizzards, caused 60 percent of the population to flee for a better life. Many ended up on the Pacific Coast.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/27-0852M-79865f40e75d49e8a59b78e830a569d2.jpg)

The drought, dust storms, and boll weevils that attacked Southern crops in the 1930s, all worked together to destroy farms in the South.

Outside the Dust Bowl, where farms and ranches were abandoned, other farm families had their own share of woes. Without crops to sell, farmers could not make money to feed their families nor to pay their mortgages. Many were forced to sell the land and find another way of life.

Generally, this was the result of foreclosure because the farmer had taken out loans for land or machinery in the prosperous 1920s but was unable to keep up the payments after the Depression hit, and the bank foreclosed on the farm. Farm foreclosures were rampant during the Great Depression.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gd15-58b974ce3df78c353cdca424.gif)

The vast migration that occurred as the result of the Dust Bowl in the Great Plains and the farm foreclosures of the Midwest has been dramatized in movies and books so that many Americans of later generations are familiar with this story. One of the most famous of these is the novel "The Grapes of Wrath" by John Steinbeck, which tells the story of the Joad family and their long trek from Oklahoma's Dust Bowl to California during the Great Depression. The book, published in 1939, won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a movie in 1940 that starred Henry Fonda.

Many in California, themselves struggling with the ravages of the Great Depression, did not appreciate the influx of these needy people and began calling them the derogatory names of "Okies" and "Arkies" (for those from Oklahoma and Arkansas, respectively).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/27-0695M-51199c9e84084b03b46cc86b0c3c8141.jpg)

In 1929, before the crash of the stock market that marked the beginning of the Great Depression, the unemployment rate in the United States was 3.14 percent. In 1933, in the depths of the Depression, 24.75 percent of the labor force was unemployed. Despite the significant attempts at economic recovery by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal, real change only came with World War II.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gd27-56a48a463df78cf77282dfa8.gif)

Because so many were unemployed, charitable organizations opened soup kitchens and breadlines to feed the many hungry families brought to their knees by the Great Depression.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Civilian_Conservation_Corps_-_NARA_-_195531.tif-289b4477dc6a4920b21b748d5375b595.jpg)

The Civilian Conservation Corps was part of FDR's New Deal. It was formed in March 1933 and promoted environmental conservation as it gave work and meaning to many who were unemployed. Members of the corps planted trees, dug canals and ditches, built wildlife shelters, restored historic battlefields and stocked lakes and rivers with fish.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Children_of_rehabilitation_clinic_in_Arkansas_-_NARA_-_195844.tif-0f040e271c5c47af96f241b5cbbce58b.jpg)

Sharecroppers, even before the Great Depression, often found it difficult to earn enough money to feed their children. When the Great Depression hit, this became worse.

This particular touching picture shows two young, barefoot boys whose family has been struggling to feed them. During the Great Depression, many young children got sick or even died from malnutrition.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Farm_Security_Administration_School_in_Alabama_-_NARA_-_195852.tif-131b9a4c86ed4e6184743a6d38561d66.jpg)

In the South, some children of sharecroppers were able to periodically attend school but often had to walk several miles each way to get there.

These schools were small, often only one-room schoolhouses with all levels and ages in one room with a single teacher.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Farm_Security_Administration-_Suppertime__for_the_westward_migration_-_NARA_-_195510.tif-56ba810ad7714014a2d64eec491e9b9a.jpg)

Adults and children alike were needed to make the household function, with children working alongside their parents both inside the house and out in the fields.

This young girl, wearing just a simple shift and no shoes, is making dinner for her family.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Farm_Security_Administration_Christmas_dinner_in_the_home_of_Earl_Pauley_near_Smithland_Iowa_-_NARA_-_196624.tif-d709f307e4614bf8bde156642bbf8242.jpg)

For sharecroppers, Christmas did not mean lots of decoration, twinkling lights, large trees, or huge meals.

This family shares a simple meal together, happy to have food. Notice that they don't own enough chairs or a large enough table for them all to sit down together for a meal.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Farm_Security_Administration_Migrant_worker_on_California_highway_-_NARA_-_196260.tif-01ef929aa18345fd88f1b64eb64d903f.jpg)

With their farms gone, some men struck out alone in the hopes that they could somehow find somewhere that would offer them a job.

While some traveled the rails, hopping from city to city, others went to California in the hopes that there was some farm work to do.

Taking with them only what they could carry, they tried their best to provide for their family -- often without success.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Farm_Security_Administration_Homeless_family_tenant_farmers_in_1936_-_NARA_-_195511.tif-258c563bb0e243b3b943b7125287086a.jpg)

While some men went out alone, others traveled with their entire families. With no home and no work, these families packed only what they could carry and hit the road, hoping to find somewhere that could provide them a job and a way for them to stay together.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gdliveoutcar-58b974c95f9b58af5c48ca97.jpg)

Having left their dying farms behind, these farmers are now migrants, driving up and down California searching for work. Living out of their car, this family hopes to soon find work that will sustain them.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gdsquatter-58b974be3df78c353cdca1db.jpg)

Some migrant workers made more "permanent" housing for themselves out of cardboard, sheet metal, wood scraps, sheets, and any other items they could scavenge.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/8a25193v-86cdbb1abfcc42febc456b56be72d6f2.jpg)

Migrant workers lived in their temporary shelters, cooking and washing there as well. This little girl is standing next to an outdoor stove, a pail, and other household supplies.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/8b38193v-11d70c0398c44069a7d313860773afc9.jpg)

Collections of temporary housing structures such as these are usually called shantytowns, but during the Great Depression, they were given the nickname "Hoovervilles" after President Herbert Hoover.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Depression_Breadlines-long_line_of_people_waiting_to_be_fed_New_York_City_in_the_absence_of_substantial_government..._-_NARA_-_196506.tif-23305d763d554473bcfea0b46715d5fd.jpg)

Large cities were not immune to the hardships and struggles of the Great Depression. Many people lost their jobs and, unable to feed themselves or their families, stood in long breadlines.

These were the lucky ones, however, for the breadlines (also called soup kitchens) were run by private charities and they did not have enough money or supplies to feed all of the unemployed.

This is the front cover of the song sheet for Banish the Budget Blues by Jack Lumsdaine, printed in blue, red and pink and priced at 2 shillings. An article from The Daily Guardian is used as an image. The headlines are partly obscured, but relate to taxation issues. They are: 'Tariff is more than ...', 'Huge increases in direct ... and other taxation', 'Incomes, Imports, and Stamp slugs to bring in another £12,500,000' and 'Scullin must have £14,038,770'. A caricature of a singing taxpayer, 'Peter Paytax', appears in an inset box.

This spoken word gramophone disc recording is a four-minute New Year address by Prime Minister Joseph Lyons to the Australian people. It was broadcast on 12 December 1934 by the Australian Broadcasting Commission (the ABC). Lyons’s speech reviews the previous year. Written during the Great Depression, Lyons acknowledges the suffering and sorrow that some people have experienced. He expresses faith in the public and asks them to place their faith in their leaders. The speech concludes with a quote by Robert Louis Stevenson about the importance of hope.

Lyons's speech was seen as an unusually honest assessment of the past year. The Labor Daily newspaper, generally a critic of Lyons's conservative United Australia Party (UAP) government, described it as 'the most extraordinary broadcast address of all time'.

This broadcast attempted to address the despair felt by many Australians during the period of the nation's greatest economic hardship. The global Great Depression, which had followed the collapse of the Wall Street stock market in 1929, caused bank failures, a collapse of investment, mounting unemployment, falling commodity prices and sharp falls in international trade.

The Great Depression had caused many Australians to lose their jobs in an era in which government benefits for the unemployed were limited, causing significant poverty and hardship. By mid-1932, 29 per cent of the Australian workforce was unemployed and many Australian families were forced to live in exceptionally difficult circumstances, losing homes and income.

Lyons encourages his audience to be hopeful but he gives few reasons for feeling optimistic. Lyons's government believed in the importance of repaying international debt and in balancing the budget. Economists such as John Maynard Keynes advocated deficit financing—stimulating the economy through government spending and paying back the debt when the economy recovered. Lyons’s government disagreed with this approach, however, and recovery, while steady, was therefore slow during his terms in office.

Lyons had been acting federal Treasurer for a short period in the Scullin Labor government (1929–32) but he left in 1931 because of intra-party disagreements about how to deal with the economic crisis. The Scullin government was divided between those who advocated increased government spending, those who believed Australia should default on its international debt and Lyons's own more orthodox and cautious views.

Lyons became Prime Minister in 1932 as the leader of the newly formed UAP, which brought together former Labor Party members who preferred a more conservative approach to the economy, and the Nationalist Party.

Dubbed 'Honest Joe', Joseph Lyons (Prime Minister from 1932 to 1939) was popular with the electorate and widely seen as pursuing a safe fiscal policy. He made this speech about three months after his victory in the September 1934 federal election, the second of three consecutive terms. By 1937, the year Lyons won his third term, unemployment had dropped to below 10 per cent. Although this was still high, and many Australians continued to endure hardship, Lyons was given credit for the improvement.

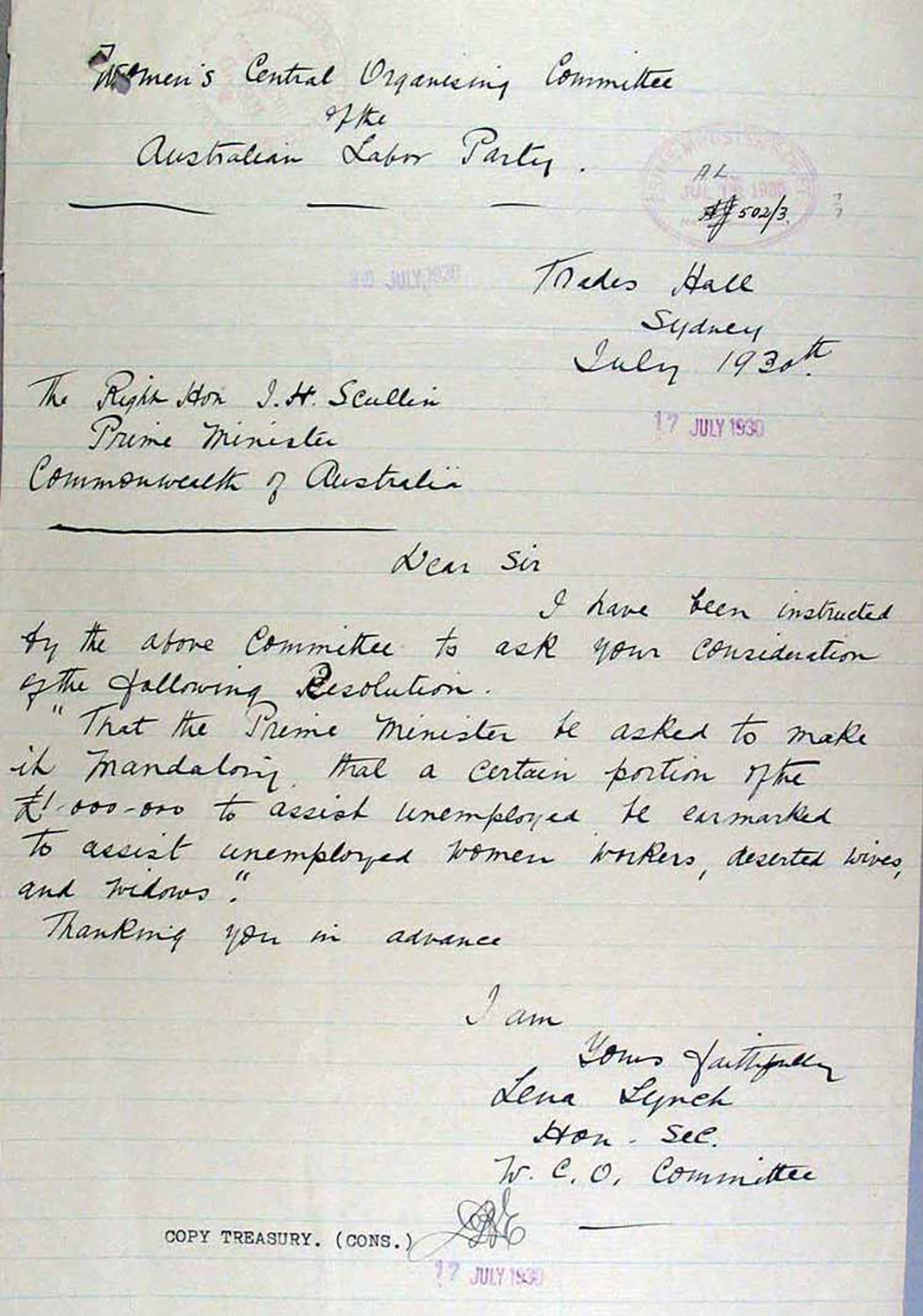

Request for financial assistance for unemployed women, deserted wives and widows – letter to Prime Minister James Scullin.

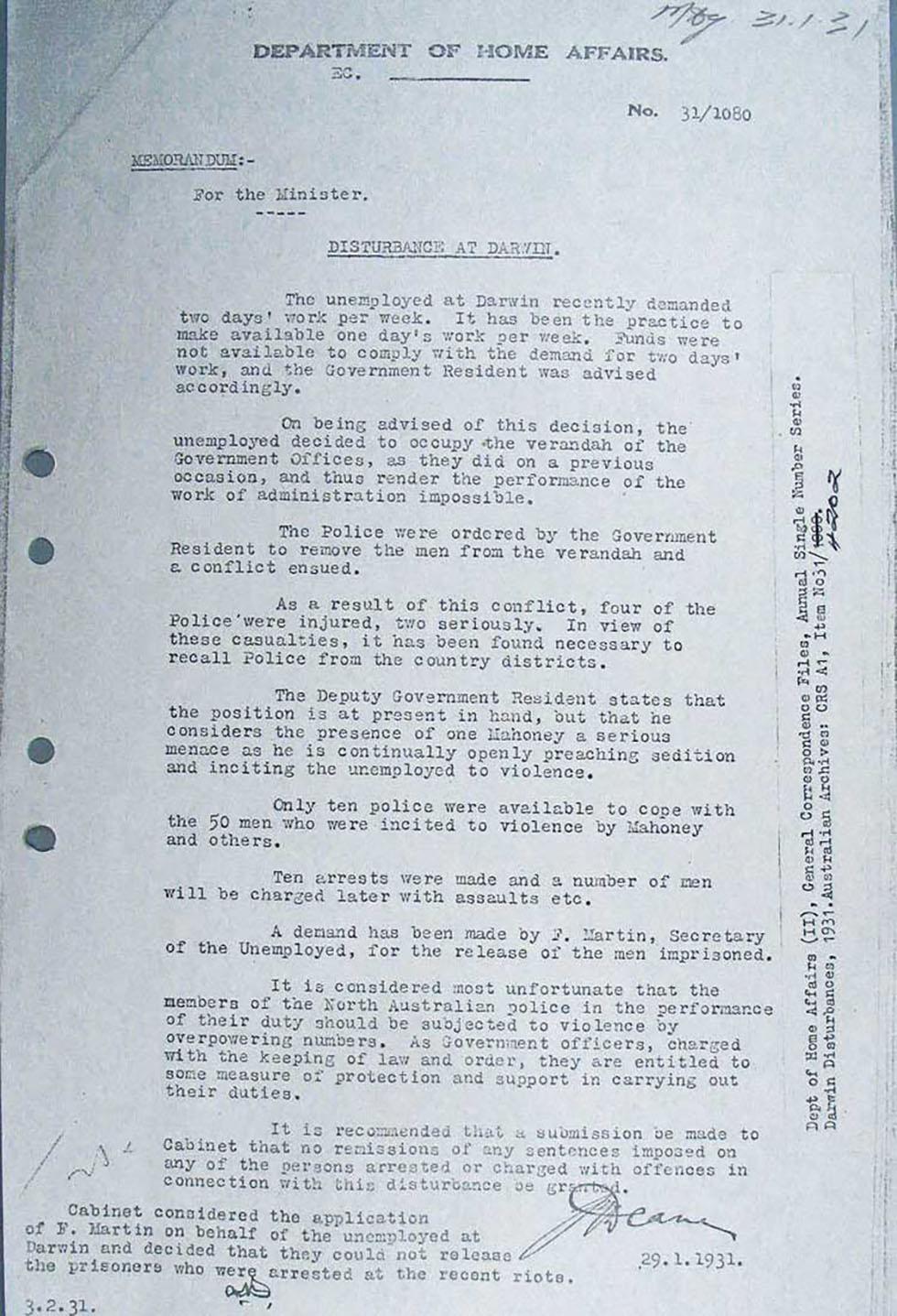

This is a typed memorandum issued from the office of the Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs and addressed to the minister, Arthur Blakely, discussing recent demands in Darwin by unemployed workers for two days of work per week. At the time, the Northern Territory was administered by the federal government. The memo is typed on a single page with a signature at the bottom. The main body of text is dated '29.1.1931'. On the bottom left of the page is an added typed note dated '3.2.31' which has been initialled. The full signature is that of Percy Edgar Deane, a senior officer with the Department of Home Affairs.

The great depression

by

The great depression

by

The great depression

by

The great depression

by

The great depression : 1929-1939

by

The great depression : 1929-1939

by

The Great Depression : what can we learn from the Great Depression?

by

The Great Depression : what can we learn from the Great Depression?

by

The human face of the great depression

by

The human face of the great depression

by