Source: IVolunteer International

Source: IVolunteer International

In Western societies, the 1920s was a decade of progress and backlash against years of trauma and deprivation caused by World War One and the 1918 flu epidemic. While many countries battled with the fallout from the collapse of empire, revolution and the ongoing impact of colonialism, the US and Europe enjoyed an unprecedented period of creativity and innovation. Cities were growing at breakneck speed, the mass production of cars was transforming both daily life and urban planning, gender norms were being questioned and racial prejudices challenged. A newly awakened thirst for life was quenched in the jazz-filled clubs of Montmartre and the decadent nightclubs of Berlin. Read through the resources below to learn more about this decade and its implication for World War II.

Nicknamed “Lady Day”, Billie Holiday started singing in night clubs in Harlem. After being heard there she was signed to a record label. She is considered iconic and known for wearing gardenias in her hair and tilting her head back while she sang.

Langston Hughes was one of the most important writers and thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance, which was the African American artistic movement in the 1920s that celebrated black life and culture. Hughes's creative genius was influenced by his life in New York City's Harlem, a primarily African American neighborhood.

Aaron Douglas, widely acknowledged as one of the most accomplished and influential visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Topeka, Kansas, on May 26, 1899. He attended a segregated primary school, McKinley Elementary, and Topeka High School, which was integrated. Following graduation, Douglas worked in a glass factory and later in a steel foundry to earn money for college. In 1918 he enrolled at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and in 1922 earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts. The following year he accepted a teaching position at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri, where he served as instructor of art for two years. A serious reader from boyhood, Douglas kept abreast of the growing cultural movement in Harlem through the pages of two influential periodicals: The Crisis, published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, and Opportunity, the monthly publication of the National Urban League edited by Charles S. Johnson. Word of Douglas’s talent and ambition soon reached influential figures in Harlem, including Johnson, who was actively recruiting young African American writers, poets, and artists from across the country to come to New York. In 1924, Ethel Nance, Johnson’s secretary, wrote to Douglas encouraging him to come east. Initially Douglas declined, but the following spring, at the conclusion of the school year, he resigned his teaching position and traveled to New York.

Douglas arrived in Harlem shortly after the publication of what was immediately recognized as a landmark publication: the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic titled, “Harlem: Mecca for the New Negro.” This special issue included an introductory essay by Alain Locke, intellectual founder of the New Negro movement, with additional essays by other progressive African American leaders. When interviewed late in his career, Douglas declared that the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic was the single most important factor in his decision to move to New York.

Welcomed by the leaders of the New Negro initiative, Douglas enjoyed the support of both Johnson, who arranged for him to study with German émigré artist Fritz Winold Reiss (American, 1888 - 1953), and Du Bois, who gave him a job in the mailroom of The Crisis. Encouraged by Locke, Reiss, Du Bois, and others to study African art as a rich source of cultural identity, Douglas also absorbed the lessons of European modernism as he forged his own visual language. Soon illustrations by Douglas began to appear in Opportunity and The Crisis. In the fall of 1925, an expanded edition of the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic was published in book form. Titled The New Negro: An Interpretation, the anthology included illustrations by Reiss and his new student, Douglas.

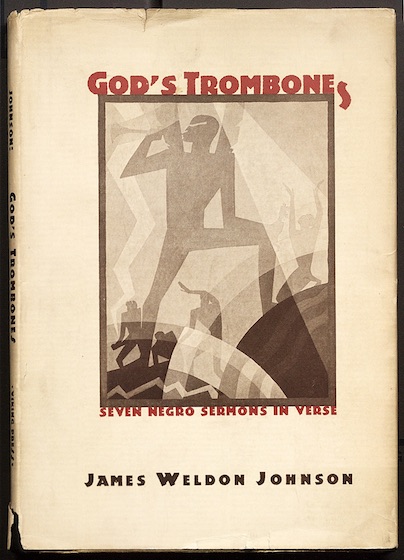

In 1927 Du Bois invited Douglas to join the staff of The Crisis as their art critic. That same year James Weldon Johnson, poet and New Negro activist, asked the young artist to illustrate his forthcoming collection of poems, God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. Critically praised, God’s Trombones was Johnson’s masterwork and a breakthrough publication for Douglas. In his illustrations for this publication, and later in paintings and murals, Douglas drew upon his study of African art and his understanding of the intersection of cubism and art deco to create a style that soon became the visual signature of the Harlem Renaissance.

Numerous commissions followed the publication of God’s Trombones, including an invitation from Fisk University in Nashville to create a mural cycle for the new campus library. In September 1931 Douglas sailed for Paris, where he undertook additional formal training and met expatriate artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859 - 1937). Following a year abroad, Douglas returned to New York, where he continued to receive commissions and, in 1933, mounted his first solo exhibition at Caz Delbo Gallery. In 1936 Douglas completed a four panel mural for the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Only two panels from this set survive. One of these, Into Bondage, is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

During the 1930s Douglas returned intermittently to Fisk where he served as assistant professor of art education; in 1940 he accepted a full-time position in the art department. Although teaching in Nashville, Douglas and his wife, Alta, retained their apartment in Harlem, where they remained active in Harlem’s cultural community—albeit now a community severely impacted by the Great Depression. In 1944 Douglas completed a master of arts degree at Teachers College, Columbia University. At Fisk he became chairman of the art department, where he mentored several generations of students before retiring in 1966. In 1970 Douglas returned to Topeka, his hometown, for the first retrospective exhibition of his work at the Mulvane Art Center. The following year he was honored with a second retrospective at Fisk. Douglas died in Nashville in 1979 at age 80.

Two artists collaborated on this famous Harlem Renaissance–era book, which combines interpretations of biblical parables written in contemporary verse with bold illustrations that echo the power and symbolism of the words.

The writer James Weldon Johnson, author, poet, essayist, and chronicler of Black Manhattan (the title of one of his books), commissioned Aaron Douglas to illustrate God’s Trombones. The book is organized into eight chapters: an explanatory preface by Johnson and introductory prayer followed by seven sermon-poems entitled “The Creation,” “The Prodigal Son,” “Go Down Death—A Funeral Sermon,” “Noah Built the Ark,” “The Crucifixion,” “Let My People Go,” and “The Judgment Day.” Each sermon adopts the vernacular of an African American preacher and is accompanied by dynamic, black-and-white illustrations that cast the stories in a contemporary light and feature black protagonists. Douglas’s painting style used bold coloration, but printing processes of the 1920s made color illustrations difficult and costly, which is why the illustrations are monochrome with text offset in a single color.

Richmond Barthé sculpted African American subjects in a sensitive, realist style. Barthé followed a classical style in sculpture, believing that any subject could be dignified and beautiful if rendered with skill and thoughtfulness. Up until the Harlem Renaissance, African American faces rarely appeared as the central subject of visual art. Barthé’s art and interest in the male figure was informed by his identity as a gay man, who according to the times was constrained in disclosing this part of his life openly, although he did find fellowship and love interests among the period’s artists and intellectuals.

Barthé grew up in New Orleans and headed north with the support of his family to pursue an artistic education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where he studied painting. At the time, SAIC and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts were the two US art schools that admitted African American students. Barthé discovered his talent for sculpture in 1927, when he was introduced to the medium during a class assignment to create a portrait bust of a fellow student in clay (he completed two). These initial works were noticed by the instructor and included in an exhibition, The Negro in Art Week, launching Barthé’s career and lifelong commitment to sculpture.

In 1930, Werner Drewes emigrated to New York City from Germany, where he had been an art student. This work is from the same year he arrived in New York and pays homage to African American womanhood and beauty. The image, created by a white artist who worked in circles outside of Harlem, attests to the widespread cultural impact of the Harlem Renaissance, of interest to people across racial and social lines, including artists, teachers, patrons, and funders who engaged in pluralist, interracial dialogues. Drewes occasionally made images of people and scenes in Harlem and other New York locations. Harlem Beauty has a timeless and sculptural quality, with its stripped-down focus on the woman’s illuminated face in profile, a classical portrait style. Drewes, like Fritz Winold Reiss, was associated with a modernist European tradition that likewise was of interest to many African American artists during the Harlem Renaissance. Can you think of other examples of cultural dialogue, wherein seemingly distinct populations influence each other’s artistic practices?

Drewes worked in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) artist employment programs as an art teacher at the Brooklyn Museum and Columbia University. He later headed the graphic arts division of the Federal Art Project, part of the WPA, in New York state. He was a prolific printmaker and, later, painter.

Hale Woodruff, alongside Aaron Douglas, Richmond Barthé, and Archibald John Motley Jr., is among the major visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Robert Blackburn, an African American artist also credited for this work, founded the Printmaking Workshop in New York, where he taught lithography and printed editions for artists, such as this one. All of the aforementioned artists were born and lived outside New York, but ultimately relocated to Harlem, drawn by its magnetic art scene. In so doing, they joined many African Americans in the northward exodus that became known as the Great Migration. Woodruff studied art at Harvard University and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as working in Paris, where he embraced modern styles of painting. In addition, he studied with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, whom he admired for the social justice themes he pursued in his art.

Sunday Promenade, part of a series of work Woodruff made while living in Atlanta during the Depression, depicts two couples and a woman wearing their Sunday best. A church lies behind them in a point at the top of the composition and underscores the centrality of spiritual life in the African American community. The turned-out appearance of the promenaders contrasts with the modest wooden structures also pictured. Woodruff also made politically charged work that dealt graphically with lynching, an issue he felt compelled to confront with his art. During the first part of the 20th century, the NAACP and other groups worked to advance anti-lynching legislation, which was never passed.

James Van Der Zee opened the Guarantee Portrait Studio in Harlem in 1917. He captured the faces and lives of people who lived in Harlem: its famous entertainers, artists, leaders, and a growing black middle class. He also took his camera to the places they called their own: homes, billiard halls, barbershops, churches, and clubs. Van Der Zee’s work forms an important chronicle of black life of the period. This well-dressed family was associated with Marcus Garvey’s movement, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). UNIA advocated for black Americans (and others from the African diaspora) to emigrate to Africa to populate and further develop Liberia, the only non-colonial state on the continent. Van Der Zee was hired by the UNIA to record and document its marches, parades, and members, who adopted a quasi-militaristic appearance. The UNIA became a mass movement of over 200,000 members during the 1920s, a time when the Ku Klux Klan had reemerged as a white nationalist group. Garvey was convicted of mail fraud in 1927 and deported to his native Jamaica. Absent his leadership, the movement faded.

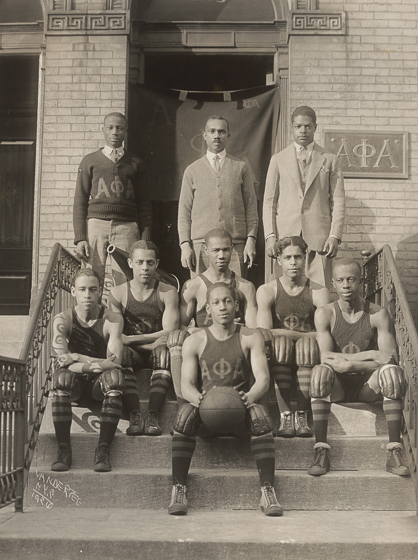

This portrait of a college basketball team shows a serious group of young men united by their affiliation with their fraternity and its basketball team. Alpha Phi Alpha was the first intercollegiate African American fraternity in the United States, its first chapter founded in 1906 at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The fraternity provided support, study groups, and, later, opportunities to participate in intercollegiate sports at a time when black players were not permitted on college teams. Note how each player is carefully posed and forms a symmetrical arrangement on the steps of the fraternity, showing their integrity as a group while radiating their determination to succeed in a racially divided country.

Like Aaron Douglas, Norman Lewis was attuned to the importance of jazz and blues music, especially growing up in Harlem during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance. Only 19 when he created this print, the work shows a modern, abstract quality while capturing visually the sense of music produced by this quartet of musicians, who seem to bob in the space of the picture, emulating the rhythm of the music.

Lewis was influenced by the writings of Alain Locke, an intellectual, impresario, and leader of the Harlem Renaissance who advocated for black visual artists to explore the distinctive character of their experience and culture. Jazz is a hybrid art form with many influences, including West African music. In 1935, Lewis viewed African Negro Art, an early American exhibition (at the Museum of Modern Art, New York) of African sculpture, textiles, and objects shown as aesthetic works of art rather than ethnographic artifacts. Lewis then began a phase of drawing imagined African masks (see the associated Pinterest board for an example). The masklike appearance of the figures in this work may also have been influenced by the exhibition.

Lewis’s printmaking activity over the course of his career was limited; he made prints for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (FAP) during the Depression years and several editions independently in the 1940s, after which he returned to printmaking only sporadically. After the 1940s, Lewis embraced abstraction in his art and became well-known in the 1950s and beyond for his large-scale paintings, one of which is also in the National Gallery of Art collection (see the related Pinterest board). He is also notable among the artists who took part in the FAP—as printmakers, muralists, and teachers—who later became prominent abstract artists, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Jacob Lawrence.

A black and white photograph of Duke Ellington with composer Billy Strayhorn and dancer Alfredo Gustar inside the Stanley Theatre in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Ellington is seated at a piano and Gustar is sitting on top. Strayhorn stands to the side of the piano, between the other two men.

Duke Ellington (among other artists) played a major role in the development of the Harlem Renaissance. He was a Jazz artist who played with a big band in popular clubs such as the Cotton club. He composed thousands of songs and is noted as a key figure in the history and development of jazz music.

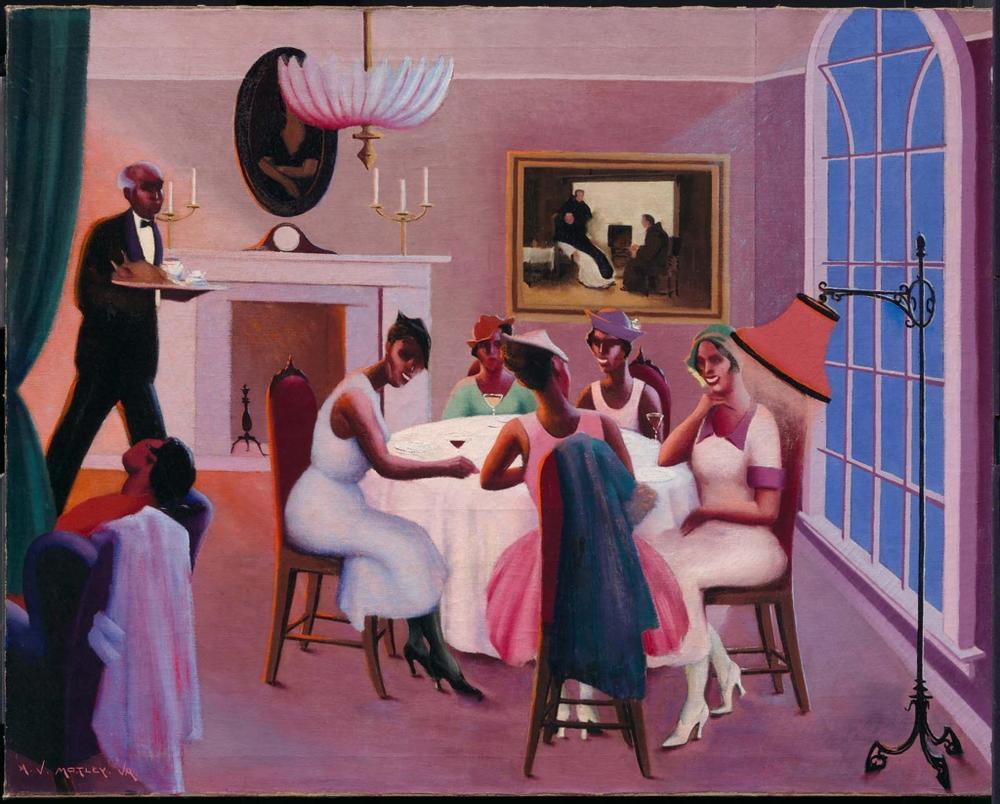

Archibald Motley, the first African American artist to present a major solo exhibition in New York City, was one of the most prominent figures to emerge from the black arts movement known as the Harlem Renaissance. Although he lived and worked in Chicago (a city integrally tied to the movement), Motley offered a perspective on urban black life that resonated nationally with all Americans who identified with philosopher Alain Locke’s notion of the “New Negro,” as popularized by Locke’s 1925 anthology, The New Negro. In America, wrote Locke, “[t]he day of ‘aunties,’ ‘uncles’ and ‘mammies’ is equally gone. Uncle Tom and Sambo have passed on” and have been replaced by “renewed self-respect and self-dependence,” among African Americans [1]. Their “New Negro” is the savvy, self-aware city dweller of today. Motley’s representations of modern African Americans illustrated Locke’s ideas on black identity and race relations.

Painted soon after the publication of Locke’s era-defining book, Cocktails addresses issues characteristic of northern United States city life generally, and black life in Chicago specifically. The composition shows a gathering of African American women laughing leisurely over a round of drinks. Yet, at a time when the manufacture and sale of alcohol was illegal and speakeasies were the counterculture recreation of choice in northern cities, the scene can be read as political commentary. That the painting is entitled Cocktails intentionally brings focus to what would have been a widely debated issue for Motley’s more conservative contemporaries. Motley emphasizes this controversial theme by using a predominantly warm color palette, with an abundance of expressive reds and pinks that convey sensuality and passion. These visual suggestions of self-indulgence and physicality are further highlighted by the stark contrast of the painting hanging on the wall behind the lively women in this scene. The composition of monks facing each other echoes the scene of social interaction between Motley’s women, but it plays this image of lively female, American socializing against a representation of monastic (and masculine, European) restraint and morality (and likely also transgression, as scenes of drinking monks misbehaving were embedded in European popular culture). When paired with the dubious condition of the seemingly unconscious woman in the bottom left corner of Motley’s scene, the painting on the wall prompts the viewer to consider conflicting aspects of African American city life. The city is hedonistic yet progressive, hostile and indifferent yet cosmopolitan and modern.

This scene also raises questions about class and racial conflict. Tensions were still high after the Chicago race riot of 1919, during which dozens of people—both black and white—were killed, hundreds were injured, and about a thousand were left homeless after their homes were burned down. The riot took place within the larger context of the Great Migration of the first quarter of the twentieth century, when millions of southern blacks migrated to northern cities for better opportunities. Competition for jobs and housing in the North exacerbated pre-existing racial tensions and led to intraracial, regional conflict. Therefore, Motley’s inclusion of a working-class figure—the relatively dark-skinned waiter—within a scene of black middle-class indulgence is significant. It brings to light the problem of color and class discrimination within the increasingly socioeconomically diverse black community in Chicago. The waiter’s darker complexion also focuses attention on the physical diversity of Motley’s women, with their array of skin tones. As the artist himself stated, “in all my paintings where you see a group of people you’ll notice that they’re all a little different color . . . I try to give each one of them them character as individuals.” [2]

Motley’s use of an early modernist artistic style, with its bold use of color, lyrical lines, and flattened forms with limited modeling, invests this domestic interior scene with the excitement of his more well-known Bronzeville paintings of the early 1930s. In contrast to those depictions of lively public gatherings within the South Side African American community of Bronzeville, the relatively private scene of Cocktails serves as an appropriate setting for the internal issues that plagued Chicago’s black enclave. Thus, Cocktails, in conjunction with Motley’s later paintings of street life, demonstrates that the image of the “New Negro” conforms to no mold. It is as expressive, vibrant, and perhaps flawed, as the figures before us.

Within two years of its incorporation in 1903 the Ford Motor Company was producing 25 cars a day. Prior to the introduction of the assembly line, the record time for building one car stood at 12 hours and 13 minutes.

In 1913 Henry Ford introduced the assembly line to help reduce the cost of the already popular Model T. Instead of working on a variety of tasks to build one car, each worker remained in the same spot and performed one task for his entire shift. Here, men make gas tanks.

Under the new assembly line system, it took 1 hour and 33 minutes to produce a car, allowing Ford to produce 1,000 cars a day. In this picture, men work on dashboards c. 1918.

Despite the success that the assembly line brought to the company, many skilled workers found the work monotonous and exhausting. Pictured here are workers in the tool and die department in the pressed-steel building at the River Rouge plant.

The Volstead Act implemented and provided an enforcement apparatus for the 18th Amendment, that prohibited "the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors."

The amendment hadn't defined "intoxicating liquors," alcohol-related criminal activity, or what, if any, exceptions would be made to prohibition. These specifics were left to Congress, which passed the National Prohibition Act, often called the Volstead Act. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the bill, but it was passed again and became law on October 28, 1919, only two months before Prohibition took effect.

The Volstead Act set a strict limit on alcohol content of .5 percent; criminalized the manufacture and sale (but not the consumption) of alcoholic beverages; and allowed for home manufacture and alcohol for medicinal and religious use. It also set stiff penalties for violations. A first conviction could result in a fine up to $1,000 and imprisonment up to six months. Property used in breaking the law could be seized.

Enforcing Prohibition was difficult and expensive, however. The long coastlines and borders of the United States aided smugglers. Bootleggers devised ingenious ways and places to make and sell alcohol. Law enforcement was underfunded and sometimes corrupt. Those arrested were often low-level violators.

As the cost of prohibition enforcement rose and the organized crime and violence associated with bootlegging gained more press coverage, support grew dramatically for repealing the 18th Amendment—or at least modifying the Volstead Act. Supporters argued that making alcohol legal again would provide jobs and taxes needed during the Great Depression and re-establish respect for the law. In 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment.