Source: NAPARAZZI

Hunting spears are usually made from Tecoma vine. These vines are not straight but in fact curly. To straighten them the maker dries out the moisture by heating the branch over a small fire while it is still green. While doing this he shapes it into the form that he wants. A wooden barb is attached to the spearhead by using kangaroo (sometimes emu) sinew. the opposite end is then tapered to fit onto a spear thrower. On completion the spear is usually around 270 centimetres (9 feet) long.

A spear thrower is also commonly known as a Woomera or Miru. The spear thrower is usually made from mulga wood and has a multi-function purpose. It is however primarily designed to launch a spear. The thrower grips the end covered with spinifex resin and places the end of the spear into the small peg on the end of the woomera. The spear can then be launched with substantial power at an enemy or prey. Inserted in the spinifex resin of the handle of many spear throwers is a very sharp piece of quartz rock. This is used for cutting, shaping or sharpening. The spear thrower was also used as a fire making saw, as a receptacle of mixing ochre, in ceremonies and also to deflect spears in battle.

Shields are usually made from the bloodwood of mulga trees. Aboriginal men using very basic tools make these. They are designed to be mainly used in battle but are also used in ceremonies. Like other weapons, design varies from region to region. Many shields have traditional designs or fluting on them whilst others are just smooth.

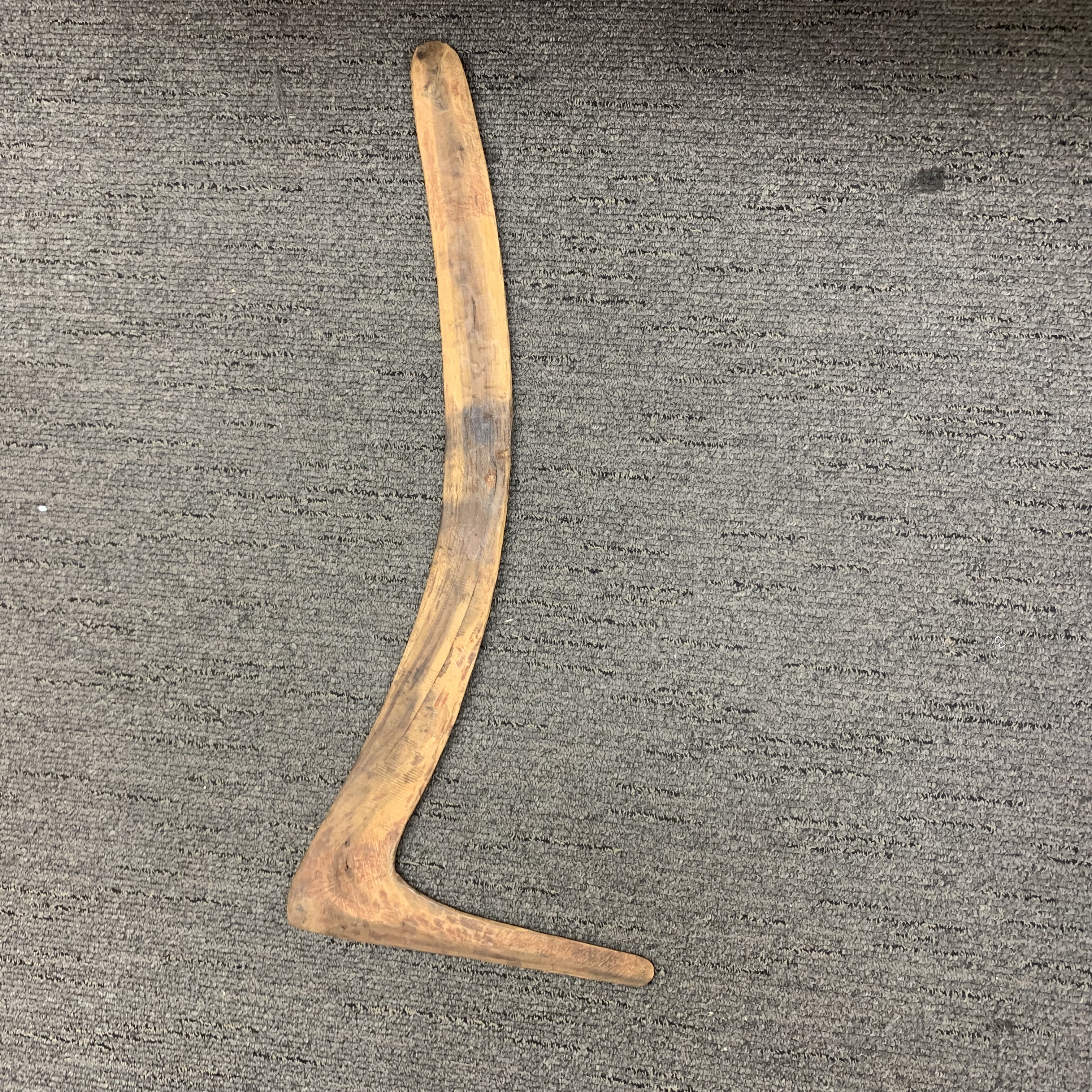

Boomerangs are also a very multi functional instrument of the Aboriginal people. Their uses include warfare, hunting prey, rituals and ceremonies, musical instruments, digging sticks and also as a hammer.

Jewellery and decorative wear is a long lasting tradition of many Indigenous nations throughout Australia that continues to be practised today. Worn by men and women, these items are worn for many reasons including ceremony, dance, initiation and/or as a way to carry sacred or healing objects. Necklace's made from Burny beans are commonly found in Far North Queensland and the Torres Strait Islands where you can collect these beans along the beach. Burny Beans also known as Velvet beans, are better known by the scientific name of Mucuna gigantea. They drop from a rampant, fast-growing vine found in monsoon forests, open forests and woodlands, riverine, littoral, subtropical and tropical rainforests. Mucuna gigantea has pale green flowers in spring and summer. The fruit is a brown, thick pod containing 4 black seeds. Brindle red and black or brown seeds can also be found, but are not nearly as common as the black. This vine is a useful screening plant and readily attracts butterflies.

Broad shields were generally used to deflect spears and their handles were either carved into the reverse side or fixed as a separate handle into holes drilled into the back. The Manna gum (Eucalyptus viminalis) was often used to make these shields, which are known by Aboriginal names such as Gee-am, Kerreem and Bam-er-ook. Tools made from stone and animal incisors (such as from marsupials) were used to engrave the surface with intricate designs.

Aboriginal people of central and northern Australia produced a variety of body ornaments for both ceremonial and decorative purposes, some were exchanged across vast trade networks, and others were 'sung' to give them certain magical powers. This forehead ornament was made using the incisor teeth of kangaroos, with each tooth being embedded in a small lump of beeswax, and then attached side by side on double-stranded string made of vegetable fibre. Among some Aboriginal groups forehead ornaments featuring kangaroo teeth were worn mostly by women. This ornament was worn with the points of the teeth hanging down. Spencer and his collaborator in Alice Springs, Frank Gillen recorded Aboriginal people using another method to make a forehead ornament with kangaroo teeth involving embedding the teeth in a small mass of resin from the leaf stalks of a species of 'Triodia', commonly known as spinifex or porcupine grass. String made from human hair was also fastened to the resin to tie behind the wearer's head. Spencer and Gillen also recorded rows of kangaroo teeth embedded in resin and tied onto Aboriginal necklets in the Northern Territory. In this case the teeth were usually coated with pipe clay to make them stand out. Animal parts were not uncommon in Aboriginal ornaments in central Australia, with a range of parts being used including bone, fur and feathers from various birds.

Stone was the heaviest and most durable material available for Aboriginal people in Australia, with sophisticated and efficient tools such as knives being made using a variety of techniques including grinding and flaking. Flaking involved the removal of controlled pieces or flakes of stone from a larger piece called a 'core.' Two basic methods of flaking include shaping the core by flaking with a hammerstone, which is usually made from a tougher rock than the core; or treating the core as a source of raw material, with the flakes being removed and used as tools, either as they come off the rock or after refinement through trimming.

Small flaked knives such as this were often equipped with a resin haft, allowing for more comfortable handling during use which included food preparation and the manufacture of implements. This hafted stone knife was obtained from a shell midden on a beach near Cape Otway in Victoria's Western District, with this area being the traditional lands of the Gadubanud peoples, commonly referred to as the 'Cape Otway people'. In 1881 amateur ethnographer James Dawson recorded the Cape Otway language group as 'Katubanuut' and asserted that this meant 'King Parrot language' in the local dialect.

Middens located along Cape Otway beaches reveal the lifestyle and varied diet of the Gadubanud including turbon shells, abalone, periwinkle, eels and ducks.

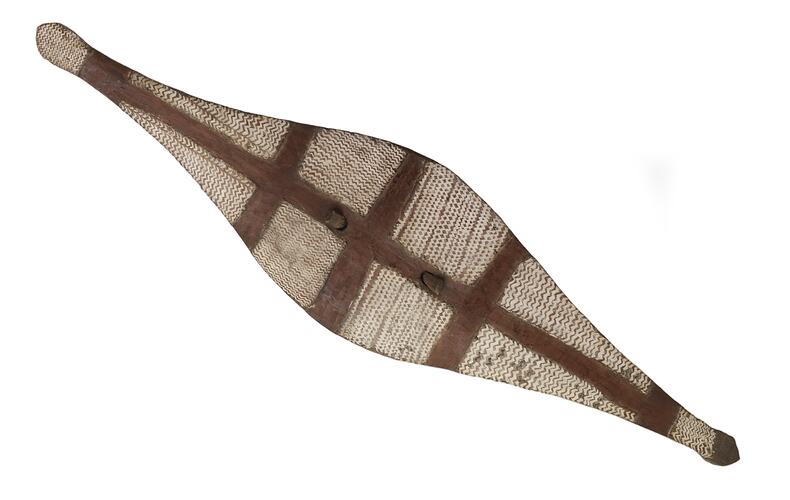

Mulga are narrow, wedge-shaped shields that were typical among many of the Victorian and South-eastern Aboriginal groups pre-contact and during early colonial times. Used during close combat, they were effective defensive weapons against clubs and other hand-held weapons. They were often made of a solid but light wood obtained from the inner timber of a tree, which was then shaped using stone tools or mussel shells.

The maker of this mulga has created a design of incised zigzag lines, and on each end a pattern of repeated broken lines. These incisions have all been filled with white pipeclay. Five horizontal bands and one running the length of the shield down the centre have been painted with red ochre. The design is visually arresting, and a dextrous warrior would use this in part to create a distracting optical illusion in battle.

Intricate designs in wood characterise the visual culture of south-eastern Australian Aboriginal people in the 19th century. The designs on all types of shields were infinitely variable, and no two are exactly the same. These designs are also used on tree carvings, possum-skin cloaks, and wooden implements and painted on the bodies of dancers. Like other art forms in the south-east the meaning of the designs is thought to relate to individual and group identity. Shields were also viewed as having innate power, and an old shield that had 'won many fights' was prized as an object of trade

Few Aboriginal stone tools found can match the level of craftsmanship of a Kimberley point and the sophisticated 'pressure-flaking' technique applied to achieve the delicate serrated edges. Before metal tools were introduced tool makers would apply pressure to the material being shaped into the point using bone points, and the Kimberley point was originally made only of stone. The use of glass and various ceramic materials become widespread following contact with Europeans in the late nineteenth century as these were easier materials to work with. One of the main uses was as a spearhead and because of their low weight compared to other spearheads, they could be attached with a small piece of resin to long, slender and light wooden shafts that could be launched at high speed during hunting and fighting. The point would often disengage from the shaft when it hit the target. They were also used as knives to cut up meat for example, and were sometimes used in ceremonies including circumcisions. Some Kimberley points were believed to have magical properties with at least one group using them in sorcery rituals designed to inflict harm on enemies. A dwindling number of craftsmen in a few remote Aboriginal communities still manufacture these points today.

Kimberley points were traded between Aboriginal groups over vast areas of Australia, and ended up in the Northern Territory and as far east as central Queensland. The edges were protected by wrapping them in wallets made of strips of paperbark (Melaleuca leucodendron) and at times further protected with bird down, fur or bulrushes. It appears that Kimberley blades have been made for more than 1,000 years with radiocarbon dates of 1020 to 1760 BP for material from sites where archaeologists have recovered stone Kimberley blades. Thousands of Kimberley points can be found in public museum and private collections today thought to be due in part to high production in the 1900s to satisfy the demand from collectors.

The provenance of this axe-head is unknown, but it may have been collected in the Hoptoun area of northwest Victoria which is the traditional lands of the Wergaia peoples. The Wergaia language was originally spoken over a wide area in the north-west of Victoria. The speakers of Wergaia and several smaller associated groups formed the Wotjobaluk groups of tribes. There is a large amount of language information for the Wergaia Language groups because of the work undertaken by the Moravian Mission at Ebeneezer. Currently the Wotjobaluk groups are working towards publishing a Wergaia Dictionary which was developed with many members of their community and Elders in 2009.

This axe-head is made from greenstone - a rock typically dark green in colour due to the high chlorite content - which was often selected for making tools as it is tough and easy to grind. Much of Victoria's greenstone can be traced to Wil-im-ee Moor-ring (Woi Wurrung language for tomahawk place) also known as Mount William. Wil-im-ee Moor-ring is one of Victoria's six greenstone quarries which are in a formation aligned north to south throughout central Victoria. Greenstone hatchet heads were prestigious items traded over much of south-eastern Australia, creating social links and obligations between neighbouring groups. The greenstone originating from Wil-im-ee Moor-ring had a wide distribution reaching a distance of up to 800 kilometres, and can be traced northwards across the Murray, up the Darling River as far as Broken Hill, across western Victoria into South Australia and to the mouth of the Murray River.

Many stone tools used by Aboriginal peoples throughout Australia were 'hafted' - a technique which involves fitting the tool with a handle, usually made from a supple piece of wood, vine or cane around the body of an axe-head, and tying the two ends together with sinew or handspun string. Resin created from plants such as spinifex, or native bees wax, were also used to further secure the head and handle. Hafted axes or hatchets were used to open hollow logs to retrieve possums, birds or 'sugarbag' (native honey), or to cut toe-holds in tree trunks.

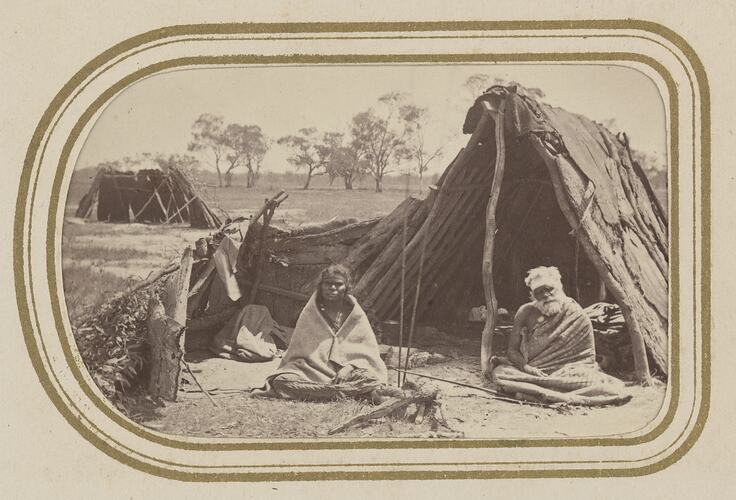

A man and a woman seated at the entrance of a shelter made of bark with a windbreak added to one side. Another shelter can be seen in the background. The woman is wrapped in a blanket and the man is wearing a possum skin cloak with the fur on the inside. Using a zoom feature and focusing on the man's cloak reveals a design that is perfectly regular in its chequered pattern. Both are wearing headbands. Two spears stand upright, with a third resting on the ground next to what seems to be campfire that is yet to be lit. Original print from the R.E. Johns album. Written in front of album is: 'R.E. Johns from Hudson Williamson, Barkly, Victoria, 1862. The handwritten entry in the index at the front the of the album provides a the following information: 'Aboriginal Hut, or Gunyah, at Cobrain, New South Wales 1868'. No other information regarding their names or the photographer's name has been recorded. The locality has been noted in the caption however this may refer to either Cobran, NSW or Cobram, Victoria. The dates entered into the index along side each entry most likely refers to the the date the photograph was created or added to the album.

Aboriginal people throughout south-eastern and western Australia wore skin cloaks, as these temperate zones were much cooler than the northern parts of Australia. The cloaks were made from the skins of possums, kangaroos, wallabies and other fur bearing animals. Early European observations noted that many of the local Aboriginal people wore skin cloaks. These observations were recorded in literature, paintings and photography.

Skin cloaks were often the main items of clothing worn by Aboriginal people in the cooler temperate zones. The cloak was worn by placing it over one shoulder and under the other it was then fastened at the neck using a small piece of bone or wood. By wearing the cloak this way it allowed for movement of both arms without any restrictions and allowed for daily activities to be carried out with ease. The cloaks were worn both with the fur on the outside and on the inside depending on the weather conditions. If it was raining the fur would be worn on the outside, providing the same waterproof qualities it did to the animal from which the skins came. The cloaks were also used as rugs to sleep on at night. Many women wore cloaks that had a special pouch at the back in which they could easily carry a small child. This is illustrated in the photo to the right of Nahraminyeri, a Ngarrindjeri woman from Point McLeay in South Australia; this photo was taken in about 1880.

When wearing the fur on the inside the spectacular designs incised onto the skin could be seen and this is well illustrated in the paintings of Aboriginal artist William Barak. Barak's paintings illustrate the magnificent designs that the cloaks were decorated with. Many of his paintings depict ceremonies with people singing and dancing in their cloaks.

Worn by women dancing in a corroboree, the emu-feather waist ornament is made from bundles of six or more emu feathers tied together. Once the feathers were secured into small bundles, they were then tied to a thin string-belt made from European fibre. Pre-contact, the string-belt was made using kangaroo sinews and a very fine cord made from possum fur; the same style of skirt was also made with alternating emu feathers and possum tails to create a thicker, shorter garment.

The biggest estate on Earth how Aborigines made Australia

by

The biggest estate on Earth how Aborigines made Australia

by

Young dark emu : a truer history

by

Young dark emu : a truer history

by

Bindi

by

Bindi

by