One of the main features of the Industrial Revolution was the horrendous working conditions that people faced. At the time, industrial cities and towns grew dramatically due to the migration of farmers and their families who were looking for work in the newly developed factories and mines. These factories and mines were dangerous and unforgiving places to work in. The working conditions that working-class people faced were known to include: long hours of work (12-16 hour shifts), low wages that barely covered the cost of living, dangerous and dirty conditions and workplaces with little or no worker rights. Look through the resources below to learn more about the working conditions during the Industrial Revolution.

This articles from History Crunch examines some of the working conditions during the Industrial Revolution, and the reasons behind these conditions.

Industrial Revolution working conditions were extremely dangerous for many reasons, namely the underdeveloped technology that was prone to breaking and even fires, and the lack of safety protocol. But it was dangerous particularly for reasons of economics: owners were under no regulations and did not have a financial reason to protect their workers. This article lists a number of the common dangers faced by workers during the Industrial Revolution.

Working today is usually quite safe. The government has made laws saying that employers have to look after the workforce and provide safety equipment and other things for them. At the start of the Industrial Revolution none of these laws existed and so working in a factory could prove to be very dangerous indeed. This website looks at some of the conditions faced by workers and offers a brief explanation of what was done to improve these conditions.

During the Industrial Revolution, laborers in factories, mills, and mines worked long hours under very dangerous conditions, though historians continue to debate the extent to which those conditions worsened the fate of the worker in pre-industrial society. This website provides a list of key points and terms about these working conditions, and also focuses on the labour of women.

The shift from working at home to working in factories in the early 18th century brought with it a new system of working. Long working hours, fines and low wages were rife in the workplace. This website provides easy to read dot points about labour conditions in factories and mines, as well as a glossary of terms.

The result of a three-year investigation into working conditions in mines and factories in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, the Report of the Children’s Employment Commission is one of the most important documents in British industrial history. Comprising thousands of pages of oral testimony (sometimes from children as young as five), the report’s findings shocked society and swiftly led to legislation to secure minimum safety standards in mines and factories, as well as general controls on the employment of children.

Britain had a long tradition of agricultural child labour, in which children were most often employed to scare crows or lead animals to pasture. With the rise of industrialisation, and particularly the development of coalmining, more children began entering the workforce at an earlier age. Children were on average five times cheaper to employ than adults, and were expected to work the same hours – which, in mining communities, could mean a 14-hour day. The Commission also uncovered many cases in which children had been used to climb into the workings of industrial machinery to clear a jam, sometimes with fatal consequences.

The Commission was established Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, with the report compiled by Richard Henry Horne, a friend of Charles Dickens and sometime contributor to Dickens’s Daily News. The report inspired protest literature from the likes of Benjamin Disraeli, Elizabeth Gaskell, Elizabeth Barrett Browning ('The Cry of the Children') and Dickens himself – most notably in A Christmas Carol.

Many workhouses were established following the Poor Law amendments of 1834, which stated that 'no able bodied person was to receive money or other help from Poor Law Authorities except in a workhouse'. This chart shows the kind of work that inmates were forced to carry out in workhouses around the country, including stone-breaking or oakum-picking - unravelling lengths of tarred rope, for use in calking the seams of battleships. For all this, the pauper received only an allowance of coarse bread; 4 pounds a week if he was married, plus 2 pounds for each child.

Life in the early 1800s was miserable for those born into poverty. ‘Benefits’ were scant, haphazardly organised by local parishes, and the cost resented by taxpayers. The Poor Laws of 1834 centralised the existing workhouse system both to cut costs and discourage perceived laziness. They resulted in the infamous workhouses of the early Victorian period: bleak places of forced labour and starvation rations, and a frequent subject for popular music and literature – notably Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens (1812–1870), first published fully in 1838.

The example of ‘workhouse art’ here is a ‘broadside ballad’: a narrative song, often setting new words on a topical subject, printed cheaply on a single sheet of large-format paper (a ‘broadside’ or ‘broadsheet’) and sold by street sellers.

Coal-fired steam engines powered England's booming economy, whether in factories or on the rail network. Those in power made huge fortunes from coal discovered under their land. Conditions in coal mines were terrible. Women and children were employed to pull the wagons of coal from the coal face to the shaft foot - these workers were smaller, and cheaper, than a properly trained horse. Various methods of ventilating mines were invented, but none was widely adopted until 1849 when compressed air first became possible. Ten years later the employment of children under 12 was made illegal.

This broadside reports a terrible explosion in a Staffordshire coalmine in which 25 lives were lost. The accompanying poem renders the scene in horrific, shocking detail: ‘With mangled flesh and broken bones/The air was fill’d with cries and groans’.

The Poor Man’s Guardian was the weekly newspaper of The Poor Man’s Guardian Society, a campaigning organisation dedicated to exposing examples of neglect and cruelty towards the poor. The Society was founded in response to the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which restricted the freedom of charities and local governments to aid the poor of their districts as they saw fit. The Act was fundamental in the construction of new workhouses throughout Britain: giant labour factories with attached dormitories, in which the poorest were obliged to live and work rather than remain illegally in the streets. Being moved to a workhouse meant long hours of menial labour in poor and unsanitary conditions, very often miles from home and family.

Charles Cochrane’s report, published here, indicates the relationship between charity and economics, as in the case of the St Marylebone parish who were attempting to reduce the cost of relief – by reducing the numbers of people applying for relief. The parish was prepared to publish the names of those applying for poor relief, ‘in order that the parishioners might by personal inspection inquire into their characters and condition, and learn whether they are deserving of the relief afforded'. Cochrane suggests that people were literally being turned away from the crowded workhouse onto the streets.

London Labour and the London Poor is a vivid oral account of London’s working classes in the mid-19th century. Taking the form of verbatim interviews that carefully preserve the grammar and pronunciation of every interviewee, the completed four-volume work amounts to some two million words: an exhaustive anecdotal report on almost every aspect of working life in London.

In his introduction to the book, Henry Mayhew (1812-87) writes: ‘I shall consider the whole of the metropolitan poor under three separate phases, according as they will work, they can’t work, and they won’t work.’ Thus, the book proceeds from interviews with working-class professionals (dockers, factory workers) to street performers and river scavengers (‘mudlarks’) and finally to interviews with beggars, prostitutes and pickpockets.

In its comprehensiveness and documentary honesty, London Labour and the London Poor was adopted as a key text by social reformers of all stripes: Christians, Whigs, liberal conservatives and socialists. A sometime editor of the satirical magazine Punch, Mayhew had been born into a conservative family, but was inspired into reforming zeal in 1849 by his experience reporting on the devastating effects on the poor of a cholera outbreak in Bermondsey, South London.

Following the establishment of the new Poor Law in 1834, a series of scandals broke, and a public backlash against the workhouse system, often from a Christian perspective, gathered momentum.

A passionate attack on the Poor Laws, Mary Wilden, a victim to the New Poor Law; or, the Malthusian and Marcusian system exposed, was written in 1839 by Samuel Roberts (1763–1848), also known as the ‘pauper’s advocate’. Roberts examines the case of Wilden, an inmate who died at Worksop Union Workhouse. Despite her horrific injuries (evidently from beatings) and a lurid catalogue of rotting skin, lice, ulcers, and being covered in her own excrement, the inquest found no evidence of mistreatment, and concluded death was by ‘natural causes’.

Roberts’s thundering polemic concludes ‘The New Poor Law and the Aristocracy cannot long exist together!’. Change came, but slowly: the workhouse system was not formally abolished until 1930, and did not finally disappear until the introduction of the welfare state in 1948.

Conditions were appalling for the 1,400 women and girls who worked at Bryant and May's match factory in Bow, east London. Low pay for a 14-hour day was cut even more if you talked or went to the toilet, and 'phossy jaw' - a horrible bone cancer caused by the cheap type of phosphorus in the matches - was common.

An article by women’s rights campaigner Annie Besant in the weekly paper, The Link, described the terrible conditions of the factory. The management was furious, but the workers refused to deny the truth of the report. When one of the workers was then fired, an immediate full-scale strike among the match girls was sparked. Public sympathy and support was enormous, surprising the management: it was an early example of what we now call a PR disaster. A few weeks later, they caved in and improved pay and conditions. A dozen years later they stopped using the lethal form of phosphorus. This article from Reynolds's Newspaper on 8 July 1888 reports on the start of the strike.

This account of a baker’s apprentice being flogged by his manager illustrates both the precariousness of working life among the young and poor in Victorian Britain and the extent to which the law newly sought to protect them. Prior to the Report of the Children’s Employment Commission of 1843 – and the associated parliamentary acts to curb employer abuses that followed – events such as those described were much more common, and practically impossible to prosecute.

Apprenticeships were an innovation of the Middle Ages whereby young people were taken on by master craftsmen or local government to learn an essential trade and ensure its continuity within the community. Apprentices were generally not paid but given food, lodgings and clothes for the duration of their study. By the Victorian Period, apprenticeships were fixed-term training schemes, usually lasting seven years, for which an apprentice’s guardian paid a premium to enrol their child. While many companies running apprenticeship schemes were honourably intentioned, a significant proportion were run as a disguised exercise in slave labour – with orphaned children being plucked from parish workhouses and induced to work long hours for free, on the grounds that an apprenticeship at least provided an opportunity to learn a trade or business.

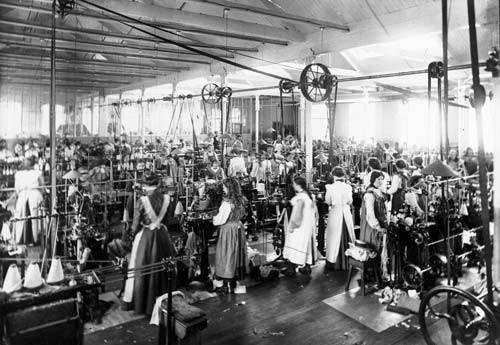

This report into a coroner’s hearing on the death of a 16-year-old factory worker illustrates some of the most common dangers of industrial production in Britain in the mid-19th century. The deceased is described as having died of ‘lockjaw’ (tetanus poisoning) having got her hand trapped in the cogs of a cotton weaving machine. A doctor amputated her finger but could not stop the infection.

Industrial accidents of this sort were very common, particularly in textile factories, where machines tended to be packed very close together with no guardrails or protective enclosures. Even leaving aside industrial accidents, cottonworks in particular were a generally deleterious environment: the moist air and ambient dust causing lung damage after long exposure, with the noise of the weaving machines often causing occupational deafness.

Life as an English farmworker in the 1830s was dismal. Rent and a basic diet of tea, bread and potatoes would cost a typical family 13 shillings a week. But exploitative landowners, given land by the Enclosures, paid their workers as little as nine, eight, even seven shillings. The Tolpuddle Martyrs were six such men from Tolpuddle, Dorset. In 1832 they founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers, demanding 10 shillings a week. A local landowner reported them, and under an obscure 1797 law they were arrested and transported to Australia. They became popular heroes, and all were released by 1837. Four returned to England. The Martyrs are still celebrated in trade union history. This article about the trial of the Tolpuddle Martyrs is from the Caledonian Mercury newspaper, published 29 March 1834.

The Poor Laws of 1834 centralised the existing workhouse system to cut the costs of poor relief and discourage perceived laziness. They resulted in the infamous workhouses of the early Victorian period: bleak places of forced labour and starvation rations.

The title page of this instructional manual – The Young Clerk’s Manual, or Counting House Assistant, published in 1848 – features a woodcut illustration of office clerks at their desk, flanked by cash and capital ledgers as though in a heraldic painting.

19th-century Britain saw the growth of what we would now call ‘white collar’ workers: people paid to oversee, administrate and annotate financial or legal transactions ordered by heads of business. With Britain’s simultaneous manufacturing and trading boom, the number of clerks in commercial industries grew enormously. The 1841 census records only 20,000 commercial clerks in Britain, but by 1871 the number of ‘clerks, accountants and bankers’ had grown to 119,000.

As the word ‘clerk’ suggests (it is Old English for ‘lettered person’, via ‘cleric’), the job mostly involved transcription. A letter from a manager would have to be copied and recopied by hand until there were enough to send to all involved parties; likewise every invoice and account ledger. A junior banking clerk at the time of this illustration would likely have earned around £100 a year. A skilled engineer might have earned double that, but because engineering was manual work and clerkship was not, the clerk was the one considered ‘middle-class’.

This is a sampler that records the sufferings of a child, working in one of the many textile mills in Salford (Greater Manchester). It was sewn by Elizabeth Hodgates who was 12 years old in 1833 and reminds us of the terrible working conditions for children, women and men during the industrial revolution.

Samplers like this were created by girls to practise their sewing skills. They also acted as decorations on the walls of the family home. In the 1800s, embroidery and needlework were regarded as an important part of a girl’s education. Sometimes they learned to sew before they could write. Different forms of needle work involved writing texts or poems, sewing numbers, figures and objects. Some samplers consisted of quotations, passages from religious texts, family trees or written memorial pieces to remember a family member.

The poem stitched in this sampler reads:

The factory child’s trouble

In the dead of the night when you take your sweet sleep

Through the dark dismal street’s to my labours I creep

To the din of the loom till my poor brain seems wild

I return an unfortunate factory child

The bright bloom of health as forsaken my cheek

My spirits are gone and my young limbs grow weak

Oh ye rich and ye mighty let sympathy mild

Appeal to your hearts for the factory child

It begs the reader to consider the plight of children who worked in Salford’s mills and factories, some aged as young as six. The second verse is suggestive of the psychological and physical damage to the child. Harsh working conditions and poor diets left these children prone to diseases such as diphtheria, typhoid and tuberculosis. Most developed lung problems through breathing in dust and cotton fragments.

In 1833, the year this sampler was made, a series of Factory Acts was drawn up to improve conditions in mills. These acts reduced working hours, increased ventilation and, importantly, improved safety for children who had to crawl underneath the working looms

In the early 1700s, work in the textile industry was mainly hand-operated and undertaken by people skilled in crafts – such as weaving and knitting. But innovations in steam power and the design of machinery in the late 18th and early 19th century transformed manufacturing and the way people worked. Much of the new labour could be undertaken by unskilled workers in factories away from the household, quicker than ever before and for a fraction of the price. Skilled textile workers, who found their livelihoods threatened by new, labour-saving technology, responded witha series of violent protests. They became known as the Luddites.

The Luddites protested by sending threatening letters to factory and mill owners and by attacking machinery. They signed their letters from Captain Ludd (or sometimes King Ludd or General Ludd), a fictitious leader named after a mythical character from the time (much like the Swing rioters who signed their letters of protest from Captain Swing). The first attacks on machinery began in 1811 when as many as 1,000 knitting-frames were destroyed in Nottinghamshire. Similar actions followed from croppers (cloth cutters) in West Yorkshire, cotton weavers in Lancashire and others across the Midlands and the North of England, and continued until 1813.

Luddism was not just a protest about machinery and mass-production. Like many others of the time, most Luddites were also protesting against high taxes, wage cuts and falling living standards in a newly-industrialising Britain. Some had political aims too, such as the reform of parliament to allow ordinary working people to vote and the right to have their voices heard. It was not coincidental that the workers mobilised during the difficult circumstances and shortages created by the Napoleonic Wars.

The authorities reacted strongly to the challenge from Luddism, they were fearful that these violent protests could escalate into a revolution like the recent French Revolution. Laws were introduced making machine-breaking punishable by the death penalty. As there was no official police service at this time, soldiers were sent to factories whose owners feared an attack. In 1812, troops killed at least 10 people when an angry crowd of around 150 Luddites attacked Rawfolds Mill in West Yorkshire. A further 17 were hanged following a highly publicised mass trial in January 1813.

Unsurprisingly, the Luddites met in secret. This simple ticket showing support for General Ludd allowed entrance to one of these meetings in the Manchester area in 1812.