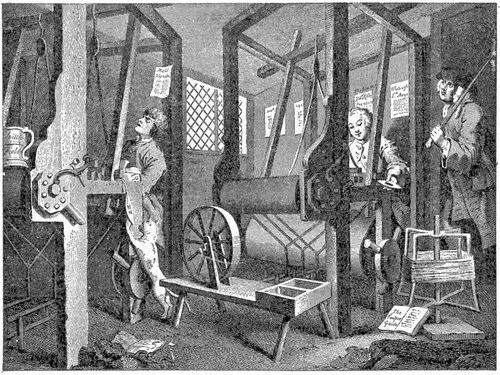

Source: Handloom weaving in 1747, from William Hogarth's Industry and Idleness

The Industrial Revolution was a time when major developments in technology were being made. Advancements in agriculture, textiles and manufacturing changed the way people lived and worked. Read more about these developments in technology with the resources below.

The Industrial Revolution (c.1760-1840) introduced many new inventions that would change the world forever. It was a time epitomised by the wide scale introduction of machinery, the transformation of cities and significant technological developments in a wide range of areas. Many modern mechanisms have their origins from this period. This article lists ten key inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

This article from Britannica lists some of the major inventors and inventions of the Industrial Revolution and their impact on society.

This website walks through some of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution, with videos and pictures to go along with the text.

This article from the British Library talks about the changes in technology and industry in Britain during Queen Victoria's reign. Links to a number of primary sources are also included in the article.

During Queen Victoria’s reign Britain was the most powerful trading nation in the world. In this article, Liza Picard explains how Victorian advances in transport and communications sparked a social, cultural and economic revolution whose effects are still evident today.

This article describes the first steam powered railway engine to run on a public railway, and how its success changed the way goods and people were transported in Britain, and how this change impacted the economy.

Click on the images below to learn more about each of these important inventions from the Industrial Revolution.

Click on the images below to learn more about each of these important inventions from the Industrial Revolution.

In the late 1830s, railways were beginning to revolutionise society. The first major line into the capital was the London and Birmingham Railway, running 112 miles (180km) from Euston to the Midlands, built by Robert Stephenson (1803–1859).

Documenting the construction process for the company from 1837 in drawings was the London artist and engraver John Cooke Bourne (1814–1896), under the sponsorship of the writer and arts patron John Britton (1771–1857).

Bourne’s fieldwork took him to the construction sites at Boxmoor, Berkhampstead, Tring, Wolverton, and most impressively, Kilsby Tunnel. A Series of Lithographed Drawings of the London & Birmingham Railway was published by Ackerman in 1838, with energetic text by Britton full of facts, figures, and enthusiasm for the new age.

Bourne’s illustrations are remarkable for their draughtsmanship and detail. They show clearly the tools and techniques that were used by the ‘navvies’ (the construction workers, from ‘navigators’, originally a canal-building term).

They are also notable for the objective view they gave of the modern world taking shape. This was no idealised portrait of innocent peasants in a timeless England, but one of engineering and progress.

The collection was critically praised and reprinted several times, and Bourne was commissioned to do similar work for the new Great Western Railway in 1843. As Britton had hoped, Bourne’s images helped counter the anti-railway lobby and promote the new railways as an exciting and positive development.

The 18th century saw the emergence of the Industrial Revolution; the great age of steam, steel and mechanised manufacturing that changed the face of the Western world forever. New weaving processes in the late 1700s allowed for the mass production of the cheap and light cloth that was highly sought after in Britain and her colonies.

New factories employed hundreds of people, including many small children, whose nimble hands made light-work of spinning. Many factories were dismal and highly dangerous, often likened to prisons, where workers encountered harsh discipline enforced by factory owners.

Numerous children were sent there from workhouses or orphanages to work long hours in hot, dusty conditions, and were forced to crawl through narrow spaces between fast-moving machinery. A working day of 12 hours was not uncommon, and accidents happened frequently. This illustration, from a 19th century book entitled History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain, might strike us as a rather sanitised portrayal of factory working conditions.

The purpose of the Great Exhibition was to showcase the best in industrial design and manufacturing across the world, with special emphasis on British invention. Its 100,000 exhibits included rail engines of every type, prototype bicycles (‘velocipedes’), raised ink (the forerunner of braille), high-speed printing presses, even papier mâché furniture. An expensive and controversial undertaking, the Exhibition was widely forecast to make a loss, which led the organising committee to spread its publicity wide. As a result, the Exhibition was one of the first public events that royalty and the working classes attended side by side.

Occupying almost 20,000 square metres in London’s Hyde Park, the structure that housed the Great Exhibition was one of the largest public buildings ever made. This guide was intended both as a means of navigating the vast site and as a souvenir for visitors.

Attracting more than six million visitors in five months, the Exhibition generated a profit of £186,000 (roughly £16,190,000). The Exhibition’s chief sponsor, Prince Albert, used this profit to establish the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington. Joseph Paxton’s elaborate plate-glass and cast-iron building – the famous Crystal Palace – was dismantled in 1852 and moved to Sydenham, South London, where it survived as a popular sporting and cultural venue before burning down in 1936.

Dating from 1885, this advertisement for Wright & Butler petroleum stoves describes them as ‘A BOON TO HOUSEWIVES’ and ‘a miracle of convenience’ – strong evidence that the stoves were intended for middle-class homes. If a middle-class Victorian husband was head of the family, his wife was head of the household. She was expected to manage all domestic arrangements from cooking, to cleaning, to laundry. Hence the appeal of the many apparently ‘labour saving’ domestic appliances that began to appear from the mid-century onwards, and the fact that most of the advertising was aimed at women.

Petroleum stoves first became available in the 1860s, but were not immediately popular. The coal-fuelled cast-iron ranges they would eventually supersede had a single significant advantage: they gave off external heat and warmed the room they were in. As this advert is keen to point out, this was not so convenient in summer. With the rise of central and storage heating in the early 20th century, stoves such as this one became standard in middle-class homes.

The first railway line in Britain opened in 1830, transforming how the public travelled and communicated.

In the 1840s, three huge scientific, technical and engineering innovations helped Britain dominate world trade. Steamships made Britain the leading maritime power; on land, railways transformed society and the economy; and the electric telegraph started the communications revolution.

This description of the new telegraph in operation comes from Household Words, a weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens (1812–1870) that ran from March 1850 to May 1859. Dickens himself describes the marvel in his leading article of the 7 December 1850 issue, ‘Wings of Wire’. Its lively reportage evokes the Victorians’s keen excitement for, and desire to embrace, the world of new technology.

In 1837 William Cooke (1806–1879) and Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875) had developed a way to control magnetic needles at the end of a wire using electric currents. By making the needles point to letters, messages could be sent instantly, whatever the length of wire. The first working system sent signals between Euston station and Camden town in north London in 1837. The telegraph then developed rapidly alongside the railway network, carrying messages and controlling signalling.

In 1851, a cable was laid across the Channel; in 1866, across the Atlantic; and by 1878, there were three links to India. News, intelligence and commands could be dispatched immediately, electronically, instead of taking days or weeks on a piece of paper. It started the modern era of instant mass communication, developing into the phone network and ultimately the internet.

While the railways were transporting people and goods around the country at unprecedented speeds in the 19th century, traffic in inner cities was becoming chaotic. The answer the Victorians came up with was simple: move the whole problem underground.

In 1863, the world’s first underground railway was built. The Metropolitan Line connected Paddington station – the London rail terminus for many prosperous commuters to the City – to Farringdon Street, just minutes from the Bank of England.

In 1891 the Central London Railway was formed to build a line connecting the City to the growing western suburbs. The line from Shepherd’s Bush to Bank was opened in 1900, and was commonly known as the 'Twopenny Line' after its standard fare.

These photographs show workers posing for the picture during the construction of the underground British Museum Station on the Central Line in 1898. This station remained in service until 1933. It was later used as an air raid shelter during the Second World War.

Photographs were initially collected by the British Museum. Despite the lack of a specific collecting policy, the Museum (part of whose collections later came to the British Library) accumulated a large number of photographic images.

In recent years the British Library has acquired two important photographic collections, the first relating to the pioneer Fox Talbot, and the second the Kodak Archive.

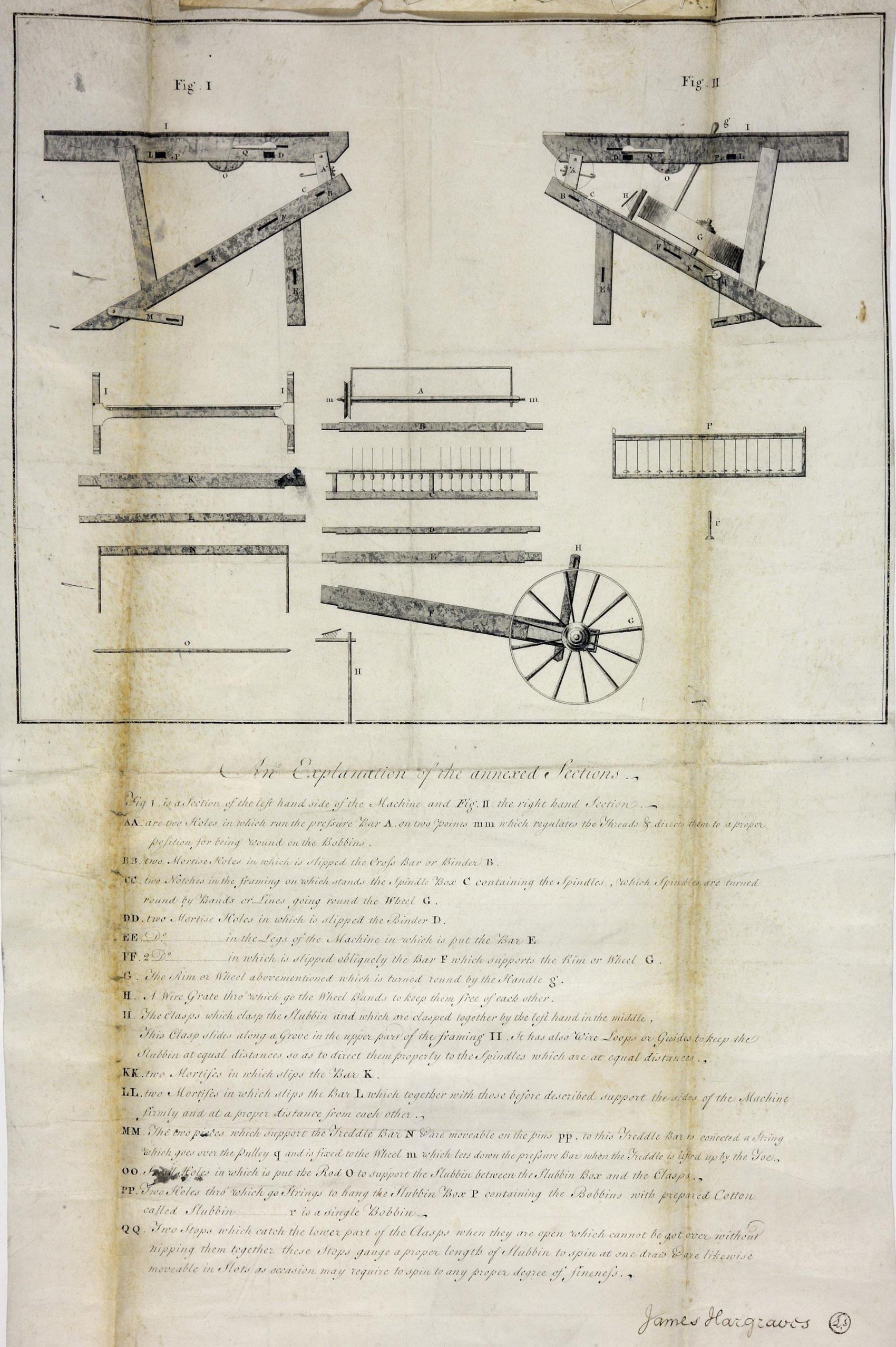

This was a multi-spindle spinning machine. It meant that a spinner could produce more yarn at a time of increased demand from weavers involved in the manufacture of cloth.