Source: Wikimedia Commons

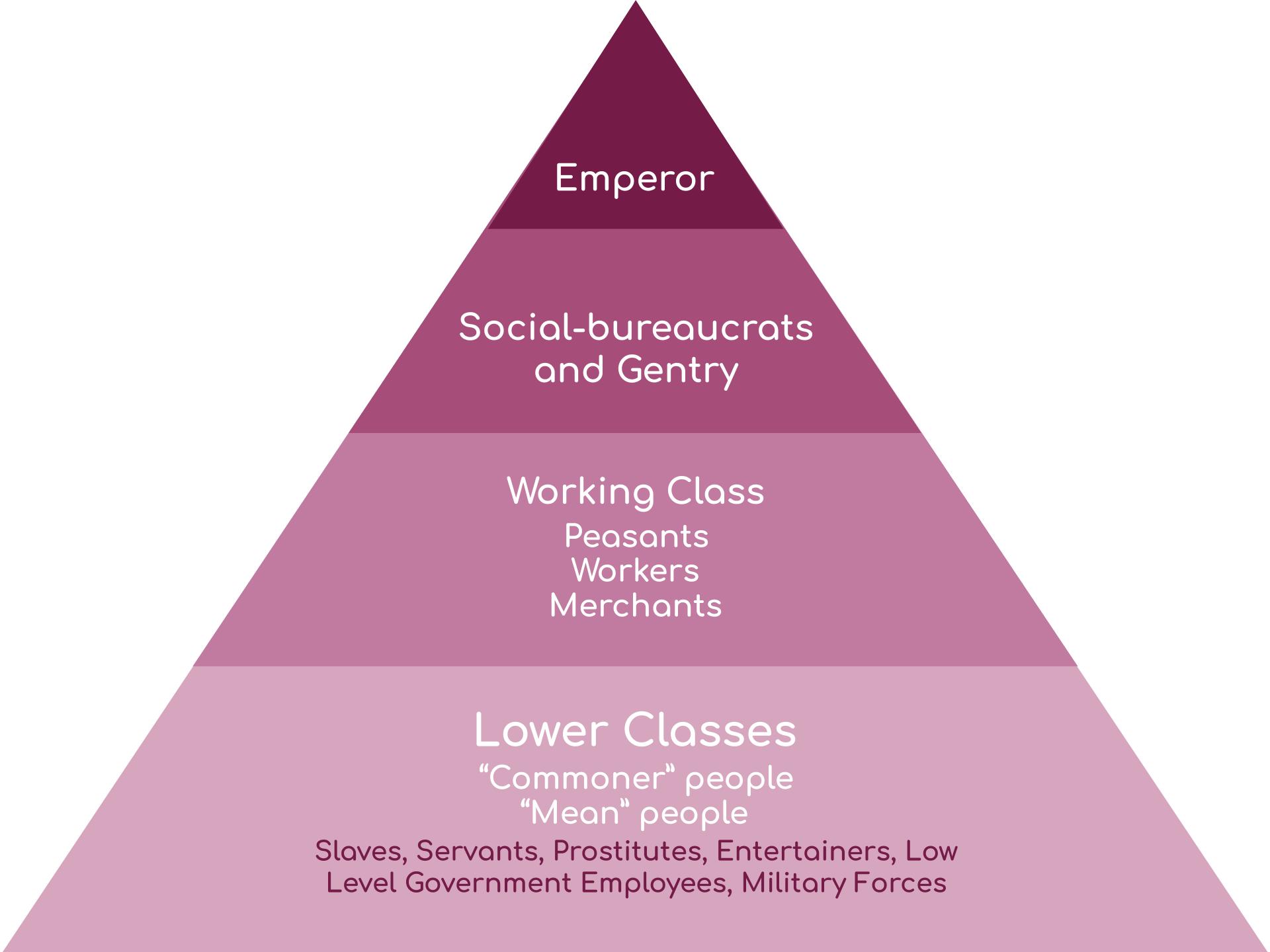

There were four social classes in ancient China including noble, farmers or peasants, artisans or craftsmen, and merchants. The four social classes were based on the teachings of Confucius. The four social classes were to allow people to live in harmony and balance. Read through the resources below to learn more.

Confucius (the Latinized version of Kong Fuzi, “master Kong”) or, to call him by his proper name, Kong Qiu (551-479 BCE) lived during the time when the Zhou kingdom had disintegrated into many de facto independent feudal states which were subject to the Zhou kings only in theory. Confucius was a man of the small feudal state of Lu. Like many other men of the educated elite class of the Eastern Zhou, Confucius traveled among the states, offering his services as a political advisor and official to feudal rulers and taking on students whom he would teach for a fee. Confucius had an unsuccessful career as a petty bureaucrat, but a highly successful one as a teacher. A couple of generations after his death, first- and second-generation students gathered accounts of Confucius’ teachings together. These anecdotes and records of short conversations go under the English title of the Analects. These Analects defined the social order in Ancient China. Click the link to read some excerpts about respect for fathers.

Confucius (the Latinized version of Kong Fuzi, “master Kong”) or, to call him by his proper name, Kong Qiu (551-479 BCE) lived at a time of political turmoil and transition. The China of his time consisted of a number of small feudal states, which, although theoretically subject to the kings of the Zhou Dynasty, were actually independent. Confucius and many of his contemporaries were concerned about the state of turmoil, competition, and warfare between the feudal states. They sought philosophical and practical solutions to the problems of government — solutions that, they hoped, would lead to a restoration of unity and stability. Confucius had no notable success as a government official, but he was renowned even in his own time as a teacher. His followers recorded his teachings a generation or two after his death, and these teachings remain influential in China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan to this day. The anecdotes and records of short conversations compiled by his disciples go under the English title of the Analects. The excerpts from the Analects in this link are specifically concerned with the problem of government.

Dong Zhongshu (c. 195–c. 105 BCE) was a renowned Confucian scholar and government official during the reign of the Han Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BCE). Emperor Wu’s reign was a defining period of the Former or Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE-8 CE), characterized by territorial expansion, rapid growth of overland trade along the “Silk Road” to Central Asia, and the consolidation of the intellectual heritage of Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, and yin-yang theory. Dong Zhongshu played a significant role in developing and articulating a philosophical synthesis which, while taking Confucianism as its basis, incorporated Daoist and Legalist ideas and the concepts of yin and yang. Dong’s thought was important in defining the roles and expectations of rulers and ministers and for making this particular version of Confucianism the orthodox philosophy of government in China.

Chinese emperors and their officials were keenly aware of the importance of the agricultural economy. A flourishing and well-managed agriculture meant a satisfied people and a large surplus, which the imperial government could use to support its rulers, bureaucrats, and armies and enable it to offer famine relief from stored grain supplies when necessary. A weak and poorly managed agricultural economy harmed not only the people, but also the emperor and his government. The Han Emperor Wen (r. 180-157 BCE) was evidently concerned about the stability and productivity of Chinese agriculture. Accordingly, he called upon his officials to devise systems of economic management that would raise productivity and increase the government’s ability to extract and store surplus grain from the rural economy. Emperor Wen issued the edict below in 163 BCE. In the edict, he describes a problem, ponders some possible causes of the problem, and asks his officials to suggest solutions. This excerpt demonstrates some of the social order in Ancient China, and the central role of agriculture in Ancient Chinese society.

Confucius (the Latinized version of Kong Fuzi, “master Kong”) or, to call him by his proper name, Kong Qiu (551-479 BCE) lived during the time when the Zhou kingdom had disintegrated into many de facto independent feudal states which were subject to the Zhou kings only in theory. Confucius was a man of the small feudal state of Lu. Like many other men of the educated elite class of the Eastern Zhou, Confucius traveled among the states, offering his services as a political advisor and official to feudal rulers and taking on students whom he would teach for a fee. Confucius had an unsuccessful career as a petty bureaucrat, but a highly successful one as a teacher. A couple of generations after his death, first- and second-generation students gathered accounts of Confucius’ teachings together. These anecdotes and records of short conversations go under the English title of the Analects. These excerpts discuss the role of women and servants in Ancient Chinese society.

Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Step into the world of Ancient China

Step into the world of Ancient China Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Ancient China by

Ancient China by  Ancient China : life, myth and art by

Ancient China : life, myth and art by  China : the world's oldest living civilization revealed by

China : the world's oldest living civilization revealed by  Life in ancient China by

Life in ancient China by  What did the Ancient Chinese do for me? by

What did the Ancient Chinese do for me? by  Your travel guide to ancient China by

Your travel guide to ancient China by