Source: Codex Mendoza, folio 70

The Aztecs were a highly developed society, with complex agricultural technology, a vibrant arts culture, and a widespread education system. To find out more about daily life during the Aztec Empire, read through the resources below.

Life for the typical person living in the Aztec Empire was hard work. As in many ancient societies the rich were able to live luxurious lives, but the common people had to work very hard. This article looks at family life, homes, clothing, food, school, marriage and entertainment in the Aztec Empire.

This article briefly describes life in the Aztec Empire, with a focus on education, work, clothing, food, farming, religion, education, and entertainment.

The Aztecs were a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican people of Central Mexico in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. They called themselves Mexica. The Republic of Mexico and its capital, Mexico City, derive their names from the word “Mexica.” This article looks at some aspects of everyday life, and includes summary notes and a list of terms for you to learn.

The Aztec civilization was also highly advanced socially, intellectually, and artistically. It was a highly structured society with a rigid caste system; at the top were nobles, while at the bottom were serfs, indentured servants, and slaves. This article looks at daily life in the Aztec Empire, with a focus on society, culture, religion, education, warfare & child life.

The Aztec civilisation, which flourished in the 14th century until the fall of the Aztec Empire in 1519, was a society based around agriculture. Most Aztecs would spent their days working their fields or cultivating food for their great capital city of Tenochtitlan. Since it was easier to grow crops than hunt, the Aztec diet was primarily plant-based and focused on a few major foods. Read this article to learn more about what the Aztecs ate and drank.

Education was an important part of daily life for the young people of the Aztec Empire. All children attended schools where they were taught the traditions and history of their people. In fact, education was free for all people regardless of their social class. This article briefly describes the education system of the Aztec empire.

A scene from the 16th century CE Florentine Codex depicting Aztec musicians. Music and dance were an important element of Aztec education and public life.

Positioned just as perfectly as part of an elegant wedding ensemble at the house of a noble family as it would have been in a grand military procession, a community-wide agricultural dance in Tenochtitlan (the ruins of which lie underneath what is now the center of modern-day Mexico City), or a rough-and-tumble sporting event at the Great Ballcourt, study of this horizontal drum reveals a succession of cultural layers, from its initial creation by a Mexica (Aztec) artist to its continued use in the colonial period (Bravo, 2018, p. 42; Castañeda and Mendoza, 1933, p. 16; Kurath and Martí, 1964, p. 47, 60, 84). Known as a teponaztli, such drums were essential to religious, military, and especially royal ceremonies.

We apply the term “Aztec,” a Western portmanteau meaning “people of Aztlan” (a mythical homeland), to a number of Nahuatl-speaking groups which were united under the rulership of the Mexica, a late-arriving but ultimately powerful group in the Valley of Mexico. This drum, likely made of extremely dense rosewood, is one of two primary types of percussion instruments in Mexica culture and consistent with those of the broader, Nahuatl-speaking world. The present teponaztli was hollowed out underneath so as to create room for the reverberations which produce its sound. Two keys or “tongues” on the top were hollowed out to different degrees in order to produce two distinct tones. Played by striking mallets on its long side, laid out horizontally on one’s lap or on a small stand (Both, 2010, p. 16), the instrument is distinct from the larger huehuetl drum, which is played by standing the object up on one of its small faces and drumming on the opposite face. Whereas the huehuetl is larger and more stationary in use, the teponaztli is quite mobile, albeit very heavy.

The cylindrical shape of this drum is fairly normative in the context of the larger corpus—some teponaztli were created in the shapes of animals. The artist added low-relief carvings onto only one side of our drum, suggesting that it was likely played with that face outward. Although very worn—evidence of substantial use—traces of depictions of flora and fauna can be seen, including rabbits, birds, and other animals. Further study may illuminate specific meanings of the imagery, including the possibility that some of the motifs refer to specific historic dates.

Its slight size belying the breadth of its capabilities, such a teponaztli would have been played using wooden mallets with rubber tips, called olmaiti (literally “rubber hands”), with the instrument sitting on one’s lap, or perhaps mounted on a simple, x-shaped stand or a more elaborate, ceremonial throne. Later iterations of teponaztli may have had more than two keys (Stevenson, 1976, p. 66). Though scholars do not agree on the gender of drummers, it is likely that both men and women in Mexica communities played the teponaztli (Kurath and Martí, p. 84). Other teponaztli are in the collections of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (including the “Tlaxcala Teponaztli” and the “Malinalco Teponaztli”); the Museo de Antropología e História, Toluca; the British Museum, London; and the American Museum of Natural History, New York. The British Museum examples include imagery of captives with turtle armbands, a horned owl (tecolotl), battle scenes with males and females, a warrior named “Five Rain,” and a glyph indicating a specific date in history.

Teponaztli were believed to be the manifestation of a court singer kidnapped by the god Tezcatlipoca and sent back to Earth in object form. As teponaztli were played, the powerful sound made manifest supernatural forces. Sixteenth-century Spanish accounts and contemporaneous codices (indigenous illustrated manuscripts) describe the contexts in which teponaztli were played, including tozohualiztli (priestly midnight household ceremonies) (Both, 2010, p. 20); xochicuicame (annual flower poetry songs) (Kurath and Martí, p. 47; Schultze and Kutscher 1957, p. 47-57); royal or imperial funerals (Casteñeda and Mendoza, 1933, p. 13; Stevenson, 1976, p. 68-69), and even wartime communication (Stevenson, 1976, p. 71). Stevenson (1976, p. 69) reports that sacrificial victims would have been slung over the drum, their hearts cut out with an obsidian knife, their blood seeping through the keys to the interior to ritually refresh the instrument. Along with the other components of ritual performance, including other instruments, costumes, and dance, teponaztli were part of a dazzling display of metaphysical theater and power.

One end of this drum is encircled by an iron band. This was likely added during colonial times (iron was introduced to the New World by the Spanish) to prevent the further expansion and splitting of the wood. Spanish priests often choreographed syncretic indigenous/European public celebrations and worship; the teponaztli would have been a means to integrate Mexica traditions into Christian doctrine and New Spanish society. These latterly-applied materials are likely evidence of that syncretism, and this drum may have been used in colonial times to link the indigenous past to a very different future.

Although numerous types of instruments survive from pre-conquest South and Central America, little is known of how they were used. Whistles, trumpets, and rattles in animal or human form probably had ceremonial functions or served as playthings. Smaller whistles in animal shapes, perhaps worn suspended from the neck, frequently have fingerholes that allow variation of pitch.

Although numerous types of instruments survive from pre-conquest South and Central America, little is known of how they were used. Whistles, trumpets, and rattles in animal or human form probably had ceremonial functions or served as playthings. Smaller whistles in animal shapes, perhaps worn suspended from the neck, frequently have fingerholes that allow variation of pitch.

This pendant, which retains the shape of a cross-section of a conch shell, features delicately incised imagery of a feathered serpent on one side, and its coiled, rattlesnake-like tail on the other. The head of the serpent, at the center of the ornament, is seen in a dorsal view, with two eyes drilled on either side of the creature’s feathered snout. The serpent’s feathered body is coiled around the center void, with two human hands emerging from either end, along with two legs at the center. Leonardo López Luján has identified the flower held in one hand as a huacalxóchitl, the Nahuatl name for Philodendron affine, a plant associated with sensuality and pleasure. (Nahuatl was the language of the Mexica, the ruling group of the Aztec Empire.) The other hand grasps what may be a knife.

This type of pendant is known as an ehecacozcatl or "wind jewel," an ornament often associated with Quetzalcoatl-Ehecatl, the creator and Wind God (for a depiction of a spider monkey wearing this regalia see accession number 2017.393). This tiny, exquisitely carved ornament contains multiple, layered meanings, from the general associations of the very material from which it was carved—shell, with its connections to warriors, and, most importantly, water and fertility—to specific associations with deities such as Quetzalcoatl. What is clear is that such ornaments were highly esteemed in Aztec times. As Adrián Velazquez Castro has noted, shell workshops were likely located within royal palaces, and their use appears to have been reserved for the private ceremonies of the Mexica elite. Such an ornament speaks to an extraordinary control over access to resources, from the raw material itself—from far away and difficult to acquire—to access to the finest artists, individuals with the skill required to transform the material into works of great beauty and delicacy.

Necklaces made of numerous small beads often in the form of animals, including shells, turtles, and frogs, are among the many types of gold ornaments worn by Aztec nobility. These creatures are all associated with water and rain and the sustenance it assures. Fertility connotations of frogs and turtles are further supported by the fact that these animals lay thousands of eggs and assume a squatting position similar to that of women in childbirth.

The ornaments were cast individually by the lost-wax process, each with its own separate clay mold which was broken after casting to release the object, explaining the slight differences in size and detail. These ornaments are said to have been found in the southern Mexico state of Chiapas.

Ancient Mexican gold objects are usually attributed to the Mixtec people, contemporaries of the Aztecs in southern Mexico. Important burials in the state of Oaxaca particularly have yielded the most impressive and technologically accomplished works in gold. The Mixtecs were renowned as the finest craftsmen in the land and perfected the art of casting from wax models. Undoubtedly their talent was much sought after by the Aztec elite. Since virtually none of the exquisite gold ornaments offered to the Spanish conquerors by the Aztecs and described by eyewitnesses survive, the distinction between Mixtec and Aztec gold objects is problematic.

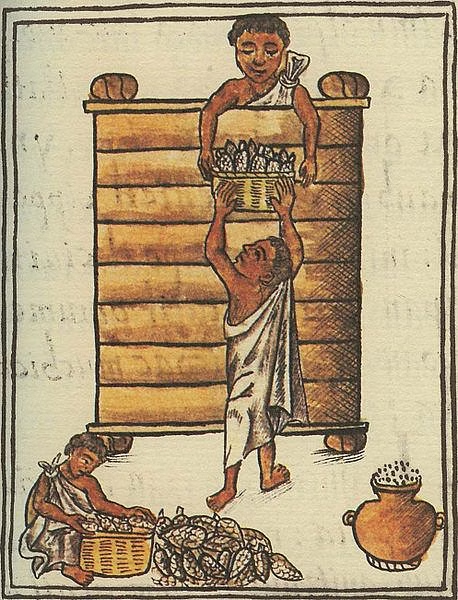

An illustration from the Florentine Codex depicting Aztecs storing maize.

By examining Aztec sculptures depicting the human form, we see a vivid and immediately recognizable portrait of daily life in a thriving metropolis. In stone and clay sculptors have depicted an urbane people in an ascendant society in a variety of poses: standing, seated, kneeling, crouching, or wearing an elaborate headdress. Some are stylized, such as fertility figures or figures of warriors; others, like the stone sculpture of a hunchback (ca. 1500), are more naturalistic, savoring the particular.

Aztec artists rarely, if ever, created realistic portraits of individuals, instead they relied on a standard repertoire of figure types and poses: seated male figure, kneeling woman, standing nude. Since the primary function of Aztec art was to convey meaning, the imagery was conventionalized. Standardized types of human figures represented rulers, warriors, priests, and a kind of everyman for commoner figures. Deities were identified by their dress and other accoutrements. Because Aztec sculpture was standardized, it is sometimes interpreted as being rigid, expressionless, stylized, conforming to a set artistic formula and established “rules” of representation.

At the same time, the Aztecs had an extensive and highly scientific understanding of the human body, and some Aztec sculptures are very naturalistic, displaying wrinkled foreheads, hunched backs, and gap-toothed grimaces as evidence that Aztec artists carefully observed their subjects.

Aztec artists did represent the human form in a wide variety of media and in a surprising range of styles. Among the most common representations in this exhibition are three-dimensional sculptures of the human form in stone and clay. These sculptures in the round represent commoners, warriors, gods, and goddesses.

For the Aztecs, the human body and spirit were intimately linked to the natural and supernatural world around them, so the state of their own being could have a direct impact on their surroundings. The aim, in all aspects of Aztec life, was to maintain natural harmony. A balanced body and life ultimately led to a balanced society and universe. Therefore moderation was advised in everything and excesses avoided for fear of upsetting the cosmic equilibrium.

This old stone hunchback with his bony rib cage and short limbs is a particularly good example of the honest and often humorous realism for which Aztec artists are today admired. He wears a loincloth and sports the hairstyle characteristic of warriors, with a lock of hair tied with cotton tassels on the right side of his head.

A painting from Codex Mendoza showing an elderly Aztec woman drinking pulque.

From the time of birth, children in Aztec, or Nahua, society were socialized into gender roles. In the birth ritual introducing the infant to society, symbolic objects clearly differentiated. Boys were to be warriors and craftsmen, and girls were to tend to domestic chores. Articles of clothing—loincloth and cape for the boy, shift and skirt for the girl—were given to the child. The umbilical cord of the boy was buried in a field to associate him with the battlefield; the girl’s cord was buried in a corner of the house, each space signifying the sites of social productivity. The image from the Codex Mendoza depicts ways in which childhood socialization patterns differed for boys and girls, systematically divided into panels on the left and right sides of the page, each vignette separated from the other by a line. In each scene, male and female adults preside over raising boys and girls, respectively. From infant to adult, children were classed into age-cohorts, each with its expectations. A ritual called izcalli took place every four years and involved a purification ceremony for children of that cohort in a fire with the acrid smoke from chili peppers. The image shows a small boy being held over the fire, the girl in front of it. Children were also held up by the head or neck to make them grow tall; their ears were pierced with maguey thorns for later ornaments. Other scarification rituals took place at various stages of maturity. After the age of four, children became responsible for gender-specific chores, and began to wear adult-like garments. They were socialized into patterns of speaking, showing respect, and sitting in gender-specific postures. Boys learned endurance, sleeping bound on the cold, wet ground; girls perfected sweeping rituals for purification of the house. The boy is taught to carry firewood, while the girl learns to grind maize and make tortillas. The image on the bottom shows an older boy learning to fish, and the girl weaving spun thread on a back-strap loom—both tasks that would require a child to reach a certain size and strength. These measures in early childhood may reflect brief life expectancies in which every member of the family had to contribute to the prosperity of the society.

Aztec children were valued creations. Language used in rituals compared infants to precious stones and feathers, flakes of stone, ornaments, or sprouts of plants. The duty of parents and society, however was not to indulge but to socialize the child, so that they would not become "fruitless trees," as an Aztec proverb stated. According to sources written shortly after the Spanish conquest, such as the Codex Mendoza, society placed a high value on conformity, obedience, and decorum. The section of the Codex Mendoza that depicts daily life shows gender-specific punishments used in raising children. The image seems to show a sequence of punishments, first threatening the boy and the girl with three maguey thorns, the spike of the agave plant. In the second image, the woman is administering punishment to the girl by piercing her arm with the maguey thorn; the boy is pierced more severely in the neck, flank, and hip, and he is bound at the wrists and ankles. In the third image, the punishment of striking the child with a stick or rod is being carried out. In each case the image shows the children weeping profusely as the threat or the punishment is administered.